|

Chapter I: Prehistoric

and Animist Periods

A.

Prehistoric Sites

1. Introduction

As infrequent archaeological excavations have slowly

revealed pieces of

Burma's past, a better but still

incomplete understanding of Burma's prehistory

has slowly emerged. Scant archaeological evidence suggests that cultures

existed in Burma as early as 11,000 BC, long before the more recent

Burmese migrations that occurred after the 8th century AD. The

conventional western divisions of prehistory into the Old Stone Age, New

Stone Age and the Iron or Metal Age are difficult to apply in Burma

because there is considerable overlap between these periods. In Burma,

most indications of early settlement have been found in the central dry

zone, where scattered sites appear in close proximity to the Irrawaddy

River. Surprisingly, the artifacts from these early cultures resemble

those from neighboring areas in

Southeast Asia as well

as India. Although these sites are situated in fertile areas,

archaeological evidence indicates that these early people were not yet

familiar with agricultural methods.

The Anyathian,

Burma's

Stone Age, existed at a time thought to parallel the lower and middle

Paleolithic in Europe.

At least six kinds of stone hand tools have been discovered in the

fourteen sites associated with this period. This assemblage of stone

tools in conjunction with additional archaeological evidence indicates

that these people lived by hunting animals and gathering wild fruits,

vegetables and root crops.

The Neolithic or New Stone Age, when plants and animals

were first domesticated and polished stone tools appeared, is evidenced in

Burma by three caves located near Taunggyi at the edge of the Shan plateau

that are dated to 10000 to 6000 BC. The most complex of these, the

Padhalin cave, contains wall paintings of animals, not unlike those found

in the Neolithic caves at Altimira, Spain or Lascaux, France. These

paintings may be interpreted as an indication that the cave was used as a

site for religious ritual. Thus, caves were among the earliest sites used

for Buddhist worship in Burma. This is of importance because the use of

caves for religious purposes continued into later periods and may be seen

as a "bridge" between

the earlier non-Burmese, Animist period and the later Buddhist period.

Numerous caves around the ancient city of Pagan have been outfitted with

Buddha images or have been incorporated into early temples such as Kyauk

Ku Umin or Thamiwhet and Hmyatha Umin.

Thamiwhet Umin, Nyaung-o, Pagan |

Buddha image erected inside Thamiwet Umin |

A Buddhist temple is referred to as a cave, whether it is

naturally formed or, as is most often the case, architecturally

constructed. The Burmese word for cave is "gu"

and has been continually used to refer to Buddhist temples. It is

frequently incorporated into the name of a temple, for example Shwe Gu Kyi

or Penatha Gu. Also, until the twelfth century, temple interiors were

intentionally dimly lit. This effect was achieved by installing permanent stone

or brick lattices in all the relatively small windows. (The Burmese ethnic

group has been credited with building their temples with larger,

unobstructed windows and thereby creating more brightly-lit interiors

- a transition that is seen in the temples of the Pagan Period).

By the second half of

the first millennium BC a new developmental phase began in the dry zone of

Burma. Referred to as the early Bronze - Iron Age, these cultures shared

practices and methods of production with various neighboring areas.

Burial methods resemble those of Thailand and Cambodia. Iron working

technology most likely came from India or other parts of Southeast Asia,

and ceramic forms and decoration correspond to those of the bronze - iron

Age levels at Ban Chiang in northern Thailand and at Samrong Sen in

Cambodia. Numerous beads have been recovered that stylistically resemble

those imported from Andrha Pradesh and Tamil Nadu in India.

2. Prehistoric: Early man at Taungthaman

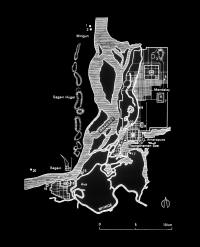

The site of Taungthaman is located near the 19th century

city of Mandalay, on an alluvial terrace of the Irrawaddy River within the

walls of the 18th century capital, Amarapura, and was occupied from the

late Neolithic through the early iron age, around the middle of the first

millennium BC. Many artifacts have been uncovered at Taungthaman such as

sophisticated stone tools, intricate ceramic wares, and primitive iron

metallurgy. Many of these objects would have been acquired from the

prosperity gained through industrious farming and trade. When burying

their dead, their new affluence encouraged these people to include among

the grave goods fine decorative ceramics produced by specialized potter

artisans as well as the more common household objects such as bowls and

spoons. Human and animal figures discovered at Taungthaman in the 1970's

are thought to have been used for religious practices. If this is so,

these artifacts represent the oldest of their kind found in Burma.

Although no building in permanent material was discovered at Taungthaman,

the excavations uncovered a pattern of post-holes that are the results of

buildings having been supported on wooden pilings.

|

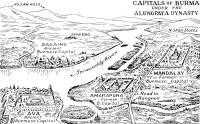

The mighty bend in the Irrawaddy inhabited since

prehistoric times |

Capitols of Burma |

Taugthaman area in annual flood |

|

Stone bracelet from Taungthaman |

Stone

hoe? from Taungthaman |

|

3. Transition to Pre-Pagan

Period

From the limited information available at present, the

evolution of these early prehistoric cultures into the later Mon and Pyu

societies is not well understood, although the late Iron Age coincided

with the rise of Pyu culture and the creation of the first cities in

Burma. However, there is ample evidence that by the fifth century AD, the

Mon as well as the Pyu peoples had adopted the Indianized cultural life

then widely practiced throughout mainland Southeast Asia which included

elements of both Hinduism (Brahamanism) as well as aspects of Theravada,

Mahayana, and Tantric Buddhism.

Bibliography- Prehistoric

Period

Aung Thaw,

'The

"Neolithic Culture of the

Padah-lin Caves",

Asian Perspectives, 14 (1971), pp. 123-133.

Ba Maw, "Research on Early

Man in Myanmar", Myanmar Historical Research

Journal, no.1 (November 1995), pp. 213-220.

Bob Hudson, "The Nyaungyan

'Goddesses': Some

Unusual Bronze Grave Goods from Upper Burma",

TAASA Review, vol 10, no 2 (June 2002), pp. 4 Ė7.

William Solheim, "New Light on a

Forgotten Past", National Geographic, vol

139, No. 3 (March 1971), pp. 330-339.

B.

Animism and the Arts

1. Animism

Animism is a generic

term used to describe the myriad religious beliefs and practices that have

been utilized in small-scale human societies since the beginning of the

prehistoric era and is the earliest identifiable form of religion found in

Burma. This is not an unexpected occurrence because animist beliefs and

practices have been found among early human societies in almost every

country of the world. Animism is a belief that spirits exist and may live

in all things, sentient and non-sentient. The world is thought to be

animated by all sorts of spirits that may intervene negatively or

positively in the affairs of men. Although spirits may live in all

things, every object does not harbor a spirit. If there were a spirit in

everything, the daily activities of mankind would be seriously disrupted

because a spirit would have to be addressed or placated at every step in a

day's activities. Spirits by their very nature

are thought to be normally invisible and to assume visible form only on

rare occasion. Therefore, it is a challenge for anyone to contact a

specific spirit and be absolutely sure that the correct spirit was

contacted and was present. Therefore, throughout the world, spirits are

often assigned a contact point where they may be enticed for

consultation. Salient features of the landscape often become the

"home" of a spirit by

assignment. Spirits are thought to live, for example, on the highest peak

in a mountain range or at the odd bend in the creek but not in every stone

or drop of water. If a landscape is devoid of a salient feature, such as

is the case with a flat rice field, one is created by assignment such as

building a simple shrine in the northeast corner of the field. That the

spirits have a recognized "home"

is important since the relevant spirit or spirits must be located and

consulted before important decisions are made or an activity undertaken.

Location as well as "presence"

is of vital importance in animism because the spirit must be agreeably

enticed to the location so that the request will meet with a

positive response. A home or locus for consulting ancestor spirits is

often created in animist societies by carving a generic but gendered human

image and wrapping it in a garment or with possessions identified with the

deceased. Gifts of all kinds, often of luxury goods, are ritually

presented to the image when it may be wrapped in any of the deceased

individual's possessions.

In virtually all

societies that practice animism, there are three broad categories of

spirits: Spirits of the Ancestors, Spirits of the Locale or Environment

(often referred to as genie of the soil) and Spirits of Nature or Natural

Phenomenon. Those individuals who were important in this life, such as

patriarchs, matriarchs, clan leaders, political leaders, or chiefs, are

honored after their death because it is believed that if they were

powerful in this life then they will be powerful in the afterlife and

consequently they should be consulted. Security for the living is achieved

and maintained by consulting these important ancestor spirits to receive

advice on major decisions and assistance to bring them to fruition.

Spirits of the locale

or environment include, for example, the spirit of the mountain, the

waterfall, the great tree or of each plot of land. In inhabited areas in

Burma and especially within villages or towns, almost every large tree has

a spirit shelf on which food and drink is placed to please the spirit and

thus assure its blessings. The small wayside shrines, typically containing

no images that are found along thoroughfares as well as in remote

locations throughout Burma are dedicated to the spirit(s) of that area,

that tract of land or that city plot.

The Spirits of Natural

Phenomenon are consulted as needed. These include the sun, moon, storms,

hurricanes, typhoons, winds and earthquakes. These spirits represent the

uncertainty of the world; that which is beyond the understanding and

complete control of the living.

Animism is typically

practiced through rituals that are performed by a specially trained

practitioner who serves as an intermediary between a person or group and

the spirit to be consulted. The term shaman -

the word used for such an individual in tribes living along the American

Northwest

Coast - is today widely employed by academics to identify such individuals

wherever they appear in the world. This practitioner is called to perform

a ritual at an auspicious location in which he entices the appropriate

spirit or spirits to appear and cooperate by flatteringly calling them by

name, performing their favorite music or songs, recounting their good

deeds and offering them the things that they enjoyed when alive, such as

food, drink (frequently alcohol), or things that have an appealing

fragrance such as flowers or incense. These "objects

of enticement" are considered by outsiders to be

the Arts of Animism. Since animist rituals often do not require an image,

these arts frequently consist of the objects used for enticement such as

fine textiles, fine basketry or fine ceramics. Typically these items are

the best available, expensive, newly made for the ceremony, or at least

refurbished since it would be offensive to offer old clothing or stale

food to a respected individual. Once the shaman is convinced the desired

spirit is present and in an agreeable mood, he goes into trance and

consults with the spirit concerning the critical matter at hand. He then

comes out of trance and shares the wishes of the spirit(s) with his

client(s).

There are typically

three categories of questions that are asked: those that involve the

security of the group or person; the fertility of humans, livestock and

crops; and the health of the group or the individual. All three

categories of questions have to do with everyday life, the here and now,

and unlike the "Great Religions",

little attention is focused on the afterlife.

The practitioners of

animism, the shaman or mediums, do not belong to an organized clergy but,

instead, learn the rituals and the practices of animism by having been an

apprentice or an acolyte to another shaman. The specialized task of the

shaman requires them to communicate with spirits, whether male or female,

while in a trance. Consequently, an individual of ambiguous gender is well

suited to speak intimately with spirits of either gender. Therefore,

shaman tends to be either effeminate males or masculine females who at

their will are capable of going into trance.

In Burma, animism has

developed into the cult of the Thirty-Seven Nats or spirits. Its spirit

practitioners, known as nat ka daws, are almost always of ambiguous

gender, and are thought to be married to a particular spirit or nat.

Despite their physical appearance and costume, however, they may be

heterosexual with a wife and family, heterosexual transvestites, or

homosexual. Being a shaman is most often a well-respected profession

because the shaman performs the functions of both a doctor and a minister,

is often paid in gold or cash, and is often unmarried with the time and

money to care for their aging parents. Shamans who combine their

profession with prostitution lose the respect of their clients

- a universal conflict and outcome. The

reputation of Burmese nat-ka-daws has been generally damaged by this

conflict.

Nat images in Nat shrine, Shwezigon Stupa,

Pagan

|

Nat images in Nat shrine, Shwezigon Stupa, Pagan

|

Animism, a generic

term for the Small Religions, is a substratum of beliefs out of which the

Great Religions have developed. It is a useful term to describe all of the

small religions that vary greatly in the specifics of their practice.

However, there are general characteristics that are easily recognized.

Since animism is based upon the worship of individuals who once lived in

addition to spirits that dwell in specific environmental locations, there

are a myriad number of spirits. These spirits change in name and function

in different physical environments. Consequently, the names of the spirits

change from valley to valley, from one village to another or from one

small group to the next. The worship of numerous spirits differs markedly

from the great religions, which usually have one all encompassing god or a

limited pantheon of gods. By comparison, in Burma and Thailand there is a

spirit attached to every parcel of land.

Since Animism is

typically practiced by non-literate groups of people, a written record of

their theology or literature doesn't exist.

Practices or beliefs are passed down orally from shaman to apprentice.

Since it is important for the shaman to preserve the correct order in

which chants and genealogies must be recited, shaman in several societies

have independently invented what scholars have come to refer to as

"memory boards". These

are boards on which there are a series of symbols or marks that assist in

proper recollection and recitation. These boards have been found in many

small-scale societies including those in Southeast Asia, particularly in

Borneo

and as far away as

Easter Island. These boards, although often undecipherable

to the uninitiated, are important because they are examples of the first

form of writing.

Art objects used in

animism are typically made of perishable materials. The images are often

of wood, cane, feathers, leather, and other materials such as unfired clay

that easily disintegrate. Due to humidity, bacteria, and the foraging of

animals and insects, these art forms do not last for long periods. Art

forms made of perishable materials are suitable for animist ritual since

the animist aesthetic places importance on the new and beautiful because

the end goal is to please and attract the spirits. The sentiment here is

that attractive gifts should be new and not secondhand. Therefore, old

images that have been used previously are frequently repainted, re-dressed

or made anew. At times, the "art objects"

are discarded after a ritual since the objects have served their purpose

of attracting the spirit and the spirit by its very nature of being a

spirit can not take the objects away.

Animist art obects are

created in almost any form. The images may be anthropomorphic, or just an

uncut slab of rock. The object may be adorned or unadorned.

In Burma, the major

Animist spirits were transformed into the Pantheon of the 37 Nats during

the Pagan Period. The earliest known images of the brother and sister nats,

Min Mahagiri and his Sister, who lead the pantheon, were painted on two

planks hewn from a their sacred tree that had been thrown into the

Irrawaddy and had floated down the Irrawaddy to Pagan.

Min Mahagiri in nat shrine, Shwezigon, Pagan |

Mahagiriís Sister, Shwemyethna, Princess Golden Face

in

nat shrine, Shwezigon Stupa, Pagan |

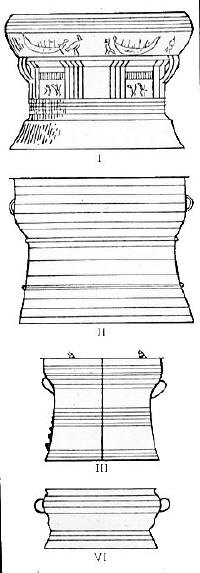

2. Bronze Drums - An

Animist Art Form

The use and manufacture of bronze drums is the oldest

continuous art tradition in Southeast Asia. It began some time before the

6th century BC in northern Vietnam and later spread to other areas such as

Burma, Thailand, Indonesia and China. The Karen adopted the use of bronze

drums at some time prior to their 8th century migration from

Yunnan into Burma where they settled and continue to live in the low

mountains along the Burma - Thailand border.

During a long period of adoption and transfer, the drum type was

progressively altered from that found in northern Vietnam (Dong Son or

Heger Type I) to produce a separate Karen type (Heger Type III). In 1904,

Franz Heger developed a categorization for the four types of bronze drums

found in Southeast Asia that is still in use today.

Hegerís four drum types |

The Karen Drum Type or Heger Type III |

The vibrating tympanum is made of bronze and is cast as a

continuous piece with the cylinder. Distinguishing features of the Karen type

include a less bulbous cylinder so that the cylinder profile is continuous

rather than being divided into three distinct parts. Type III has a

markedly protruding lip, unlike the earlier Dong Son drums. The decoration

of the tympanum continues the tradition of the Dong Son drums in having a

star shaped motif at its center with concentric circles of small,

two-dimensional motifs extending to the outer perimeter.

Tympanum of a Karen Bronze Drum |

Complete Tympanum of a Karen Drum |

Detail of Tympanum of a Karen Drum |

Detail of Tympanum of a Karen Drum |

In Burma the drums are known as frog drums (pha-si), after

the images of frogs that invariably appear at four equidistant points

around the circumference of the tympanum.

Frog on Tympanum of a Karen Drum

A Karen innovation was the addition of three-dimensional

figures to one side of the cylinder so that insects and animals, but never

humans, are often represented descending the trunk of a stylized tree.

Stylized tree with snails and elephants |

Detail of stylized tree with snails and elephants

|

Detail showing a

complex arrangement of snails, elephants, trees squirrels and other

animals. |

The frogs on the tympanum vary from one to three and, when

appearing in multiples, are stacked atop each other. The number of frogs

in each stack on the tympanum usually corresponds to the number of figures

on the cylinder such as elephants or snails. The numerous changes of motif

in the two- and three-dimensional ornamentation of the drums have been

used to establish a relative chronology for the development of the Karen

drum type over approximately one thousand years.

The Karens speak

several languages that linguists have had difficulty classifying.

Karen groups often speak different languages, some of which are not

mutually intelligible. Hence, the Karen peoples are an exception to the

basic assumption that an ethnic group can be defined by the fact that all

its members can converse in a single tongue. There are at least three

major cultural and linguistic divisions among the Karen: the Karreni or

the Red Karen, who cast the bronze drums, the Pwo Karen, and the Sgaw

Karen, as well as a number of other splinter groups who have scattered

into the mountains below the Shan Plateau.

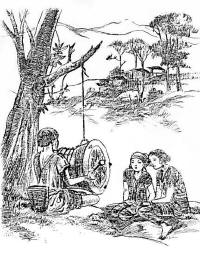

Two Red Karen Women |

A Sgaw Woman |

Two Sgaw Karen couples |

These hillside people practice swidden or slash-and-burn

agriculture and speak a language that is very different than that of the

lowland Burmese. The practice of slash-and-burn agriculture consists of

burning the forests and then using the ashes from the burnt timber as

fertilizer for the fields.

A swidden field ready for planting |

Broadcasting rice in swidden field |

The fertilizer lasts for only several years, never more

than six, and at that time the Karen must pack and move everything to a

new site where a different section of the forest is burned. A number of

hillside groups practice slash-and-burn agriculture and periodically move

through each other's hereditary territory to new lands. These people

move back and forth across the Thai border with little regard for the national boundary.

Slash-and-burn agriculture is perilous in that after the forest is burned, seeds must be planted and then rains must occur quickly and

consistently until the plants are well established. If this does not

happen, the plants will wither and die or insects and animals will eat the

seeds. It is not unusual for the Karen to be forced to plant four times

in order to reap a single harvest. For the Karen, the bronze drums

perform a vital service in inducing the spirits to bring the rains. When

there is a drought, the Karens take the drums into the fields where they

are played to make the frogs croak because the Karens believe that if the

frogs croak, it is sign that rain will surely fall. Therefore, the drums

are also known as "Karen Rain Drums"

Bronze drums were used

among the Karen as a device to assure prosperity by inducing the spirits

to bring rain, by taking the spirit of the dead into the after-fife and by

assembling groups including the ancestor spirits for funerals, marriages

and house-entering ceremonies. The drums were used to entice the spirits

of the ancestors to attend important occasions and during some rituals the

drums were the loci or seat of the spirit.

It appears that the

oldest use of the drums by the Karen was to accompany the protracted

funeral rituals performed for important individuals. The drums were played

during the various funeral events and then, among some groups, small bits

of the drum were cut away and placed in the hand of the deceased to

accompany the spirit into the afterlife. It appears that the drums were

never used as containers for secondary burial because there is no instance

where Type III drums have been unearthed or found with human remains

inside. The drums are considered so potent and powerful that they would

disrupt the daily activities of a household so when not in use, they were

placed in the forest or in caves, away from human habitation. They were

also kept in rice barns where when turned upside down they became

containers for seed rice; a practice that was thought to improve the

fertility of the rice. Also, since the drums are made of bronze, they

helped to deter predations by scavengers such as rats or mice.

When played, the drums

were strung up by a cord to a tree limb or a house beam so that the

tympanum hung at approximately a forty-five degree angle.

Karen drum being

played

The musician placed

his big toe in the lower set of lugs to stabilize the drum while striking

the tympanum with a padded mallet. Three different tones may be produced

if the tympanum is struck at the center, edge, and midpoint. The cylinder

was also struck but with long strips of stiff bamboo that produces a sound

like a snare drum. The drums were not tuned to a single scale but had

individualized sounds, hence they could be used effectively as a signal to

summon a specific group to assemble. It is said that a good drum when

struck could be heard for up to ten miles in the mountains. The drums were

played continuously for long periods of time since the Karen believe that

the tonal quality of a drum cannot be properly judged until it is played for

several hours.

The drums were a form

of currency that could be traded for slaves, goods or services and were

often used in marriage exchanges. They were also a symbol of status, and

no Karen could be considered wealthy without one. By the late nineteenth

century, some important families owned as many as thirty. The failure to

return a borrowed drum often led to internecine disputes among the Karen.

a. Animist Drums and Buddhism

Although the drums

were cast primarily for use by groups of non-Buddhist hill people, they

were used by the Buddhist kings of Burma and Thailand as musical

instruments to be played at court and as appropriate gifts to Buddhist

temples and monasteries. The first known record of the Karen drum in Burma

is found in an inscription of the Mon king Manuha at Thaton, dated 1056

AD. The word for drum in this inscription occurs in a list of musical

instruments played at court and is the compound pham klo: pham is Mon

while klo is Karen. The ritual use of Karen drums in lowland royal courts

and monasteries continued during the centuries that followed and is an

important instance of inversion of the direction in which cultural

influences usually flow from the lowlands to the hills.

b. Casting the drums

The town of Nwe Daung,

15 km south of Loikaw, capital of Kayah (formerly Karenni) State, is the

only recorded casting site in Burma. Shan craftsmen made drums there for

the Karens from approximately 1820 until the town burned in 1889.

Karen drums were cast by the lost wax technique; a characteritic that sets

them apart from the other bronze drum types that were made with moulds. A five metal formula was used

to create the alloy consisting of copper, tin, zinc, silver and gold. Most

of the material in the drums is tin and copper with only traces of silver

and gold. The Karen made several attempts in the first quarter of the

twentieth century to revive the casting of drums but none were successful.

Karen drums casting

- 1923

During the late 19th

century, non-Karen hill people, attracted to the area by the prospect of

work with British teak loggers, bought large numbers of Karen drums and

transported them to Thailand and Laos. Consequently, their owners

frequently incorrectly identify their drums as being indigenous to these

countries.

Bibliography

- Animism and the Arts

F. Heger, Alte

Metalltromeln aus Sudest-Asie (Leipzig, 1902).

H. I. Marshall, The

Karen People of

Burma: A Study in Anthropology and

Ethnology (Columbus,

1922).

H. I. Marshall,

"Karen Bronze Drums",

Journal of the Burma Research Society, xix (1929), pp. 1-14.

Richard M. Cooler,

"The Use of Karen Bronze Drums in the Royal

Courts and Buddhist Temples of Burma and Thailand: A Continuing Mon

Tradition?", Papers from a Conference on Thai

Studies in Honor of William J. Gedney (Michigan Papers on South and

Southeast Asia, No 25, Ann Arbor, 1986) pp. 107-20.

Richard M. Cooler,

The Karen Bronze Drums of

Burma: Types, Iconography,

Manufacture, and Use (Leiden,

1994). |