Chapter II

The Pre-Pagan Period:

The Urban Age of the Mon and the Pyu

A. Pre-Pagan Period: Introduction - General

History

The first millennium AD in Burmese history, The Urban Age, is

characterized by the first appearance of cities and the formation of

nation states. Of great importance in this process was the arrival from

India of

a wide variety of ideas and beliefs, both religious and secular. The

occurrence of urbanism and Indianization at this time is shared by other

polities in mainland Southeast Asia and should be considered a regional

phenomenon even though the earliest known city, Beikthano, is found in

Burma. Indeed, coins minted in Burma have been found in urban sites as

far away as northern Thailand and southern

Vietnam.

It was also during this period that sophisticated irrigation systems using

weirs were established in the central dry zone and henceforward the dry

zone remains paramount in Burmese political life and history.

As evidenced by artifacts and inscriptions, an array of religions were

practiced during the Pyu period such as Hinduism and in particular

Vaishnavism, Theravada Buddhism, Mahayanna Buddhism, Tantrayanna Buddhism

and a vast range of uncodified animist beliefs and rituals. By the end of

this period, the major Animist spirits (Nats=Burmese) had been

subordinated to Theravada Buddhism which become the religion of choice

among the lowland rice farmers and Theravda Buddhism has remained the

predominant religion in Burma until the present day.

From approximately 200 BC, a number of walled cities were built in central

Burma whose plans consisted of rounded squares or rectangles. It is

believed that circular shapes (at times oval, as in ancient Thai sites)

was an indigenous Southeast Asian creation whereas the square or mandala

plan was imported India. Upon examining aerial photographs of these cites,

it is obvious that the dichotomy between circular and square is not

clear-cut. The corners of the city walls have been rounded as well as the

entrances to the gateways and in addition, the city walls are not straight

but bulge elliptically. Some features of the Pyu cities are certainly of

Indian origin such as the use of twelve gates. Therefore the plans of

these early cities show a mixture of traits, some indigenous, some

borrowed.

Although the Burmese began to live in cities before the arrival of Indian

ideas, these foreign ideas were essential to create important capitol

cities of international and cosmological significance. The adoption of

Indian concepts of city planning incorporated a belief in the efficacy of

the world axis that connects the centermost point in a properly

constructed Mandala city with the city of the Gods above (Tavatimsa

heaven) in order to assure prosperity throughout the kingdom below.

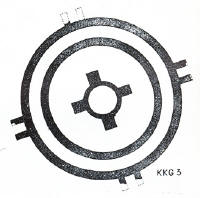

A

remarkable characteristic of the Mon and Pyu cultures is that they minted

and used silver coinage. The earliest type of these uninscribed coins

depicts a conch on one side and a Srivatsa (a door-like symbol associated

with good fortune) on the other. These coins date from the 5th century,

originated in the Pegu area, and became the model for almost all coinage in

mainland Southeast Asia during the first millennium AD. The later Pyu coins are

derived from this earlier Mon type and appear in several varieties till

the end of the 8th century AD. Many of these coins have had a

small hole punched along their perimeter so that the coins may have been

used as much for amulets as for trade. After the Pyu Period that ended in

the late 9th century, coins were not used again in the Burmese

kingdoms until the 18th century!

Pyu

coins |

B.

The Mon People of the Coastal Regions

1. General History and Introduction

The first Indianized peoples in

Burma were the Mons. An honor shared

with their northern neighbors, the Pyus. The Mons, a people of Malayo-Indonesian

stock, are related to the early inhabitants of Thailand and Cambodia who

also spoke Mon-Khmer languages. The Mons who are considered to be the

indigenous inhabitants of lower Burma, established their most significant

capital at Thaton, strategically located for trade near the Gulf of

Martaban and the Andaman Sea.

Little is known of the early history of the Mon people including how long

their various kingdoms flourished and the extent of their domains. For

example, it is not definitely known if it was the Mon or the Pyu who

controlled the lower delta region. Descriptions in Chinese and Indian

texts specify their settlement area as being around the present day cities

of

Moulmein and Pegu in the monsoonal plains of Southeast Burma. This area

was first known as Suvannabhumi ("land of gold") and later as Ramannadesa

("Land of Ramanna"); Ramanna being the word for Mon people. The area

known as Suvannanbhumi was often connected with the historical Buddha in

the later Mon and Burmese chronicles that credit the Mons

with first establishing the Buddhist religion in Burma.

Although little is known about actual religious practice, trade

connections through the Mon port city of Thaton can be traced to the

Indian kingdom of the Buddhist King Ashoka from as early as the 3rd

century BC. Legend maintains that 2,500 years ago the Mon people began the

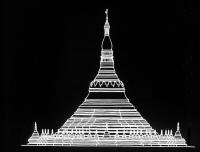

original structure of the Shwedagon Pagoda that today has become the most

revered Buddhist stupa in Burma, a true national monument. This

theory, though tenable, lacks objective corroboration because the many

changes that have been made to the pagoda over the years have repeatedly

encased its original structure and there is no contemporary record of its

foundation or a description of its form.

Plan of The Shwedagon Stupa, Rangoon |

Upper Terrace, Shwedagon, Stupa, Rangoon |

Small ShrinesUpper Terrace, Shwedagon, Stupa, Rangoon |

Once a very powerful political and cultural group, today’s Mon population

of around 1.3 million has been mostly absorbed into the mainstream of

Burmese culture. These Burmese Mons make up only a small part of the

Mon-Khmer speakers of

Southeast Asia with many of their

relatives living further to the east in Thailand and Kampuchea. Although

their culture has merged with that of the Burmese, the Mons

have continued to use their own language and since 1962 have had their own

state. As devout Buddhists, they follow their own ceremonial calendar of

Theravadin festivals. Their main source of livelihood comes from the

cultivation of rice, but they also grow other crops such as yams, sugar

cane, and pineapple.

2. Pre-Pagan Period: Thaton

a. Introduction

The early Mon kingdoms that were in power during the prehistoric period,

were situated between the Sittang and

Salween rivers and were referred to

as Ramannadesa. Thaton, the seat of this kingdom, is believed to have been

Suvannabhumi (“Golden Land”), a term that was also used to refer to the

whole region of continental

Southeast Asia

bordering the Bay of Bengal. Thaton is thought to have been founded by

King Siharaja during the lifetime of the Buddha, which would place it in

the fifth century BC. Thaton was once a flourishing port community that

communicated with and transported goods from as far away as Southern

India. Later Burmese chronicles credit the Mon people of Thaton with

bringing the Buddhist religion to Burma. In these chronicles it is also

stated that Buddhist manuscripts from Sri Lanka were translated into Mon

characters around 400 AD. Although scholars have questioned this fact, it

is known from local inscriptions that Theravada Buddhism definitely

existed in Lower Burma by the fifth century AD. Although the exact

founding date of Thaton and the extent of its kingdom has yet to be

discovered, it is known that Thaton fell under Burmese control during the

11th century when the first great King of Pagan, Anawrahta, sacked the

city and returned to Pagan with Thaton’s King Manuha as his captive.

Thaton remained under Burmese domination until the fall of Pagan in 13th

century. Thenceforth, the Mons re-established their independence, although

the capital was later moved to other locations including Marataban and

Pegu.

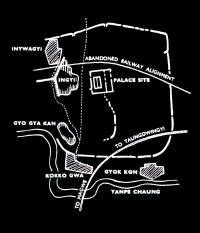

City Plan of Thaton

Thaton’s quadrangular city plan resembles that of the later Burmese cities

of Amarapura and

Mandalay. Four walls surrounded the

old city creating a rectangular shape that enclosed the walled palace

compound that was located at its center. From north to south the palace

site measured 1, 080 feet and 1, 150 feet from east to west. Two chief

stupas were situated between the palace site and the south wall. Today,

the old city of

Thaton is no longer visible as growth of the modern town

has obscured the earlier settlement.

b. Pre-Pagan Period: Thaton - Architecture

Of the two stupas situated between the palace site and south

wall, the Shwezayan is the largest. Across the road from the Shwezayan

stupa is the Kalyani Sima, a hall built especially for the ordination of

monks. On the sandstone boundary pillars that surround the Kalyani Sima,

the stories known as the Ten Great Jatakas may be seen. These carvings

illustrate the last 10 lives of the Buddha before he was reborn as Gautama,

the historical Buddha who gained enlightenment. An inscription on one of

the pillars dates them to the 11th –13th centuries.

i.

Swezayan Stupa

The original form of the Swezayan, stupa, said to have been

built in the 5th century BC, is difficult to ascertain since it has been

repeatedly rebuilt and expanded. As it stands today, the stupa has a

circular base and its overall structure resembles that of a bell. Found

within the compound of the Swezayan stupa are several inscribed stones,

five in the Mon language of the 11th century. These stones are now

preserved within the stupa compound.

Also found within the building are several stone sculptures, loosely dated

to the 10th-11th centuries. One of these is a relief carving on sandstone

of a standing Buddha. His right hand held at his side points downward with

the palm facing outward in the wish-granting gesture known as varada mudra.

His left hand is held upwards against his chest with the thumb and index

finger pressed together in the argumentative or teaching attitude known as

vitarka mudra. Above the Buddha’s shoulders are the figures of hamsa

birds facing each other.

c. Sculpture: Thaton

The relatively few pieces of sculpture that can be dated to this early

period vary greatly in style and in subject matter. The subjects portrayed

are of Hindu, Buddhist and Animist gods. Two Hindu sculptures dating to

the 9th – 10th centuries are carved from slabs of

reddish sandstone and depict in high relief the figure of Vishnu reclining

on the serpent Ananta. From his body issues a tripartite lotus stem on

which are seated Brahma, Vishnu and Siva. This configuration is peculiar

to Pyu art. In India, the usual presentation of this event shows a

single god, Brahma, appearing within a lotus flower that grows from

Vishnu’s navel.

Another Hindu sculpture is that of the four-armed Siva seated with his

vehicle, Nandi, the bull below his right leg and the buffalo-demon under

his left knee. From slightly later are two small images of Ganesa and a

small sculpture of a seated Brahma. All of these sculptures were removed

to the

Phayre Museum at

Rangoon and then loaned to the Rangoon University Library

where they were located when the Japanese destroyed the building during

World War II. Consequently, they are known today only from fragments and

photographs.

C.

The Pyu People

1. General History

The Pyu people settled inland along the middle reaches of the

Irrawaddy River

but at a distance from the river’s course. This is in sharp contrast to

the later Burmese cities such as Pagan, Ava, Amarapura, and Mandalay that

were situated directly on the riverbank. The Pyus developed a system of

irrigation using elevated weirs as well a sophisticated system of urban

planning. The Pyus adopted Buddhism as it spread into Southeast Asia while

continuing to practice animism, the worship of indigenous spirits.

Excavations at the great Pyu capitol, Srikshetra, uncovered artifacts

associated with Vishnu as well as the remains of Buddhist stupas and

monasteries that clearly indicate that Hinduism as well as Buddhism were

practiced there. Indeed, the name of the earliest Pyu city, Beikthano,

means the “City of Vishnu”, the second of the great gods in the Hindu

Triad. Due to the scarcity of written material, little is known about the

Pyu peoples themselves. Although the Pyu had a written language, few

examples still exist. The Pyu language and culture seems to have

disappeared as they were conquered and absorbed by the Burmese. The Pyu

and Burmese languages are similar, both belong to the Tibeto- Burman

family of languages. Most of what we do know of the Pyu is extrapolated

from archeological excavations, surface finds and scant references in

Chinese Dynastic Histories. Additional but very limited information is

found in the few inscriptions on burial urns that typically state the

names and reignal dates of early rulers and in the formulaic inscriptions

on Buddhist votive tablets. None of these sources yields detailed

information about the Pyu people or their culture. In fact, it wasn’t

until 1911 that the Pyu language could be read. This was the result of the

translation of the Myazedi Inscription, the Burmese “rosetta” stone. This

quadrilingual inscription, written in the Pyu, Mon, Burmese, and Pali

languages, was

erected before the (Buddhist) Myinkaba Kubyauk-gyi

Temple at Pagan in 1113 AD. That this Pagan inscription was written in

Pyu in the 12th century suggests that although Pyu culture had

declined in the 9th century due to invasions from the North by the Chinese

and had been subsequently absorbed by the Burmese, the Pyu had

continued as an important presence for over three centuries after the

Chinese invasions.

However, little is heard or known of the Pyu after the 12th century.

2. The Pyu City of Beikthano

a. Introduction:

Beikthano – 1st to 5th centuries AD.

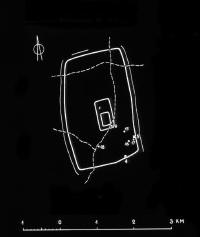

Plan of Beikthano |

One of the earliest Pyu sites is Beikthano, the City of

Vishnu, which is

situated near the east bank of the Irrawaddy River

between Srikshetra and Pagan. Little of the ancient city exists today

because its once tall brick walls were quarried to construct roads and

railway tracks. Therefore, most of what is known of Beikthano is the

result of archaeological excavations carried out in the twentieth

century. Among the excavated structures were found the ruins of Buddhist

monasteries, although no Buddhist statuary was found; two pillared halls;

four stupa–like buildings; and a city wall made of fired brick enclosing

an area of over 2.8 kilometers. The excavations produced artifacts that

can be categorized as having essentially Pyu characteristics: silver coins

bearing symbols of prosperity and good-luck, burial urns of both plain and

elaborate designs, beads of clay and semi-precious stones, decorated

domestic pottery, iron nails, and metal bosses. This assemblage of

artifacts is shared with the later Pyu cities of Halin and Srikshetra.

Through the analysis of the structures, pottery types, particular marks on

potsherds, the inscriptions on a clay seal and on burial urns, the period

in which Beikthano existed can be established as the 1st –5th

centuries AD.

b. Beikthano: City plan

The city plan of Beikthano resembles a bulging rhombus, each side of the

city wall measuring about two miles, although little remains today due to

natural decay and human depredation. Excavation revealed twelve gateways

where the walls curved inward to create entrance passages, each

terminating in massive gates. In each of these passages the burnt

remains of a wooden gate and rusted iron sockets were found. A rectangular

brick enclosure, referred to as the Palace site, lies approximately at the

center of the walled city. In the center of the eastern wall of this

palace enclosure there is an inner gateway that unlike the curved

entrances along the city walls has a square entrance. On either side of

all the excavated gates was found an indented space for guards or

sentries. Near the entrance to the palace site, two huge pairs of

feet carved in sandstone were found. Although the upper portions are

missing, these were no doubt once massive figures of door guardians.

c. Beikthano:

Architecture

Of the over one hundred debris mounds that are present at Beikthano,

twenty-five of them were excavated between 1959 and 1963 (new excavations,

it is reported, are presently underway). While artifacts, and coins have

come to light, little is known concerning the details of the physical

structures at the site since they now exist only as fragmentary

foundations. The foundations of a number buildings made of large,

kiln-fired bricks were unearthed, among them are two halls with wooden

pillars, possibly audience halls; a large rectangular monastery building

containing multiple cells; and the foundations of several circular, stupa-like

structures, a few of them situated on square bases. These stupa-like

foundations were in several cases closely associated with numerous burial

urns containing the ashes and bones of cremated human bodies.

i.

The Monastery Building

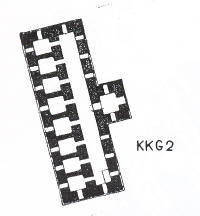

To the north of the palace site lies the most important structure at

Beikthano: a large multi-room building that was almost certainly a

monastery. The structure of the building was made of well-fired bricks

with wooden doors and window frames. This building, evidently used as a

residential dwelling for monks, was destroyed by fire as indicated by the

charred remains of its wooden fittings. The remains of the brick walls

now rise to about 8 feet. The building consisted of a main rectangular

structure measuring about 100x35 feet with a smaller rectangular

projection on the east side. The floor plan consists of ten rooms: one

entrance hall on the east occupying the projection, one long corridor hall

occupying the eastern half of the main rectangle and eight small square

rooms to the west of the long hall. The wall opposite the only exit on the

east leads to a long corridor, which is connected by a large door to all

of the small rooms. The several, small and identical rooms within this

building resemble those of Buddhist monasteries at Nagarjunakonda in

Andrha

State of South India.

Since this building is found in close proximity to one of the stupa-like

structures, it was almost certainly built as a residence for monks.

This structure can be dated by an impression in clay discovered within

that was stamped

with a circular seal containing four letters in Brahmi script that are

datable to the second century AD.

Drawing of

Beikthano monestary foundation |

Floorplan of

Beikthano monestary |

Among other structures exposed at Beikthano is a cylindrical building with

four rectangular projections outside two concentric retaining walls that

resembles the typical Andhra type of stupa found at Amaravati and

Nagarjunakonda in Southern India. The Andhra stupa type typically has

rectangular ayaka platforms that project at ground level from the cardinal

points. Here the projections are very prominent but do not support any

inscription pillars nor is the drum of the stupa decorated with sculptured

stone slabs as in the Indian prototype.

Floor plan of stupa-like building |

ii.

Stupa-like foundations

Another type of religious or ritual structure that was uncovered in three

excavations consists of a square base on which originally stood a

cylindrical structure, perhaps surmounted by a low hemispherical dome,

which would be like the stupas at Nagarjunakonda. There were no

projections from the drum itself but a rectangular wall projected from one

side only and is a feature peculiar to Beikthano. Burial urns were found

associated with these structures, though not actually enshrined within

them. The urns typically were found in groups buried along the outer

perimeter of the structures in close proximity to the square foundation

base.

An extended human skeleton and two groups of human bones were recovered

outside the south and north walls of one of these structures. It is

evident from the stratigraphy that the urns and bones were buried at the

same time in a single layer. The absence of religious objects at this site

and the definite association of the structure with burial urns as well as

human skeletons strongly suggest that the building was used for funereal

purposes.

Also unearthed were the rectangular foundations of two halls built with

brick floors having openings for wooden pillars. These are located near

buildings thought to be monastic establishments, an arrangement that also

has South Indian precedents. Importantly, the placement of burial urns

around the foundation of these structures is a trait unique to the Pyu

culture of Burma and is not found in similar structures in South India.

d.

Beikthano: Sculpture

A

distinct curiosity of this site is the lack of any evidence for Buddhist

images, although they have been found at other Pyu city sites such as

Halin and particularly Srikshetra. One proposal to explain this curiosity

has been that it is an indication that a type of aniconic Buddhism that

does not employ images was practiced here and that the practice was

similar to that of the Aparaseliya and Mahisasaka sects of South India

that do not use images. On the other hand, all evidence of images may have

vanished if they were purposely and completely destroyed and/or

transported elsewhere.

e. Beikthano: Other arts

i.

Beikthano: Burial Urns

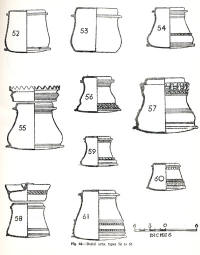

Burial Urns recovered at Beikthano |

A

wide variety of ceramic burial urns were discovered at Beikthano. Almost

all consist of a container base with a cover, though they vary

considerably in shape from spherical to water pot with neck, to

cylindrical with straight sides, to globularly cylindrical. Surface

ornamentation also varies greatly from resolutely plain to elaborate

sgrafitto and applique patterns. Most were found inside or just outside

the various structures with calcinated bones and ashes inside.

The burial urns found at Beikthano in some considerable abundance reveal

definite cultural links between Beikthano and the later Pyu sites of Halin

and Srikshetra. A great number of urns have been unearthed at Srikshetra

that show a similar pattern in their contents and their manner of burial,

however they are far less ornate in their decoration than many of the urns

at Beikthano. Although few urns have been found at Halin, their tall,

perpendicular sides are also quite similar to some of the urns found at

Beikthano.

Since the burial urns - and rarely, complete human skeletons- were found

buried in groups along the outer base of the stupa-like buildings, the urns must then have been used for secondary burials. This practice

necessitates having a place to store the cremated remains of several

individuals until a sufficient number of them are accumulated for a group

interment. Therefore, before the final burial could take place these

funeral urns appear to have been stored in religious buildings as a part

of sepulchral rites observed by the inhabitants of the Beikthano. Also,

large quantities of pottery of various types and calcified bones and

skulls were found within one of the structures unearthed at the site which

may be further evidence that it was used as a storage facility or

sepulchre for the cremated bodies awaiting burial.

ii.

Beikthano: Coins

Limited numbers of Pyu

coins -

typically marked with symbols but without

inscribed words - were found at

Bseikthano. The coins that have come to

light include types found at the later Pyu sites of Halin and Srikshetra

and thus establish an important cultural link between these Pyu sites.

3.

The

Pyu

City of Halin 2nd –6th AD

a. Halin: Introduction, General History

Halin, a Pyu city in northern Burma, is located north of Mandalay about 12

miles southeast of Shwebo and seems to have flourished from the 2nd to the

6th century AD. Preliminary excavations were carried out in 1904-5, in

1929-30 and again from 1963 to 1967. Although these excavations yielded

many small finds including burial urns, beads, shards, coins, engraved

gems, and metal implements as well as a few inscribed lines written in Pyu,

little architectural evidence other than the bases of square or

rectangular brick buildings were found. Even so, it is evident that the

remains at Halin are characteristically Pyu. That is with the exception

that no round stupas, large stone or metal images, nor clay votive tablets

were found, such as appear in some abundance at Srikshetra. A practice

prevalent at Halin that differs from Beikthano was the burial of

non-cremated human remains along with the funerary urns. The attack on

Halin in 832 AD by the Nan-chao of Yunnan, China, appears to have been a

devastating blow since according to the Chinese records the entire

population was carried off into slavery and after this date mention of the

Pyu is very rare.

b. Halin: City Plan

Of rounded rectangular shape, the brick-walled and moated city

is roughly two miles long and one mile wide. At present, the walls of the

city have crumbed almost to ground level. Most of the structures

themselves were below ground level and had to be completely uncovered

through excavation. Traces of the moat are seen on all sides except the

south. Three of the original twelve gateways were uncovered. The brick

city walls curve inwards at the onset of each entrance gateway and thus

create a protected passageway into the interior of the city. A rectangular

shaped outer wall with rounded corners was also delineated that is similar

to the city plan of Beikthano.

City Plan of Halin |

c. Halin:Architecture

The structures within the walls consist of square or rectangular buildings

that in several instances have a quadrangular projection from one side.

Earthen funerary urns were found buried both within and outside these

structures. Since these building reveal no evidence of a religious

purpose, they are thought to have been used solely to house funerary urns.

At a site situated near the “palace” a large rectangular hall made of

brick, possibly serving as an assembly hall was exposed. The charred

remains of 84 wooden pillars in four ranks are evidence of how the roof or

superstructure was originally held in place. Charred remains were

also found of the wooden gates that once stood at the entryways to the

city. An analysis of charcoal specimens from this structure thought to be an

assembly hall has produced a date of 6th century AD. Charcoal from two of

the wooden gates indicate a date to the 2nd or 3rd

century AD.

d. Halin: Other Arts

Although no Buddha images or clay votive tablets were discovered, Halin

has produced a rich trove of small artifacts. Objects such as decorated

sherds and beads of semiprecious stones, a few gold rings, two gold

pendants, two gold beads, one round and one barrel-shaped, and several

tiny disc beads of gold were found at different ritual structures. Irons

nails, knife blades, arrowheads and sockets for doors were recovered in

abundance. Of particular interest is a weapon called a caltrop made of

four, sharp, connected spikes that was used to impede the progress of

cavalry and foot soldiers. Among the domestic objects recovered were

three hand-mirrors made of bronze. Other finds, often by villagers,

consist of gold, silver, and bronze objects or ornaments but these have

frequently been melted down for the value of their metal or sold. Of

particular interest are a number of Pyu coins similar to those found at

Srikshetra. The only difference between them is that the symbol of the

rising sun seen on the Halin coins is replaced by the throne (bhadrapitha)

emblem as seen on the coins from Skrikshetra. An unusual coin type found

at Halin and rarely seen at Skrikshetra has a conch within the door-like

Srivatsa symbol. Also found were several stone slabs that unfortunately

bear only partially legible inscriptions. Of those that can be

translated, at least in part, the earliest is thought to be an epitaph

marking the site of the tomb of one Honorable Ru-ba while another gives

the name of a queen, Sri Jatrajiku.

4.

The

Pyu City State

of Srikshetra (Thirikhittaya)

a. Srikshetra: Introduction

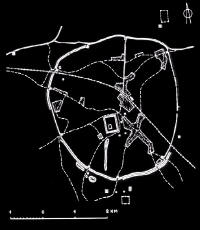

Map of Srikshetra |

Curved walls create entry passage |

The largest and most important of all the Pyu capital cites, Srikshetra,

is located approximately five miles southeast of the modern city of Prome,

180 miles northwest of Rangoon, and a few miles inland from the left bank

of the Irrawaddy. The site of Srikshetra is known by several names:

Thayekhittaya, Hmawza, and Pyi in Burmese and as Old Prome in many English

publications. This ancient capital is thought to have reached its height

from the 5th through early 9th centuries, although Pyu culture had been

developing for centuries elsewhere in

Burma.

The culture of the people who once inhabited this great city can be

ascertained through the study of architectural, sculptural, epigraphic,

and artistic remains, which are relatively abundant when compared to other

Pyu sites. Unfortunately, due to the merging of Pyu and Burmese culture,

the Pyu language ceased to be used as early as the 13th

century. Consequently, it has not been possible to decipher a great number

of the inscriptions written in Pyu. The monuments, primarily religious,

reveal a close affiliation and communication with India, but as we have

seen in other Pyu sites, very few artifacts are identical copies of an

Indian form or concept - slight to major changes set these artifacts apart

from their Indian prototypes.

It is unknown precisely when and how Srikshetra, a very prosperous city,

declined. It is thought that as the Pyus were gradually absorbed by the

Burmans as Pagan grew in importance so that by the late 11th

century Pagan had become the undisputed capitol of a unified Burma

including the formerly Pyu territories.

b. Inscriptions

The earliest known examples of writing in Burma were found at Srikshetra

and employ an alphabet that is derived from those used in South

India. Two inscribed gold plates and a manuscript inscribed on

twenty gold leaves were found in the Bawbawgyi stupa that have been dated to the

second half of the 5th century. A stone slab bearing a Pali inscription

recites in verse excerpts from Buddhist texts (the Mangala Sutta, the

Ratna Sutta, and the Mora Sutta) and can be dated epigraphically to the 6th or 7th century. Numerous

inscribed votive tablets of clay depicting figures of the Budddha have

been uncovered. Interestingly, almost all the inscribed materials relate

to Theravada Buddhism, although there are images extant from other

Buddhist sects as well as other religions.

c. Srikshetra: City

Plan

Srikshetra’s city plan, unlike that of Beikthano and Halin, is more

circular or oval in shape. The city wall of well-fired bricks is

surrounded by a moat. The circumference of the wall is eight and one half

miles and in many sections, where the wall remains intact, rises as high

as fifteen feet. At each of the entrances or gateways into the city, the

wall curves inward, as at Beikthano and Halin, to form long corridors on

either side of the entrance passages. Also, the palace site is located in

the center of the city enclosure, as found elsewhere; is rectangular in

shape and measures 1,700 feet to 1,125 feet. The northern half of the city

is a low plain dominated by rice fields but rises gradually to the south.

Chinese records state that commoners lived and farmed their fields within

the great expanse within the city walls. This report also states that the

prosperity of the city is evidenced by more than a hundred Buddhist

monasteries, decorated with gold and silver, and painted many colors that

are hung with embroidered cloth.

A

19th century Burmese Chronicle, “The Glass Palace Chronicle”

was written at the order of the Burmese king and attempts to fit

Srikshetra into the Hindu-Buddhist ideal of the perfect royal

Capitol City.

This model is based on Sudarsana, the heavenly city of Indra (shaka:

Burmese) which is located on the peak of Mount Meru at the center of the

universe. The

palace of Indra is at the center of the city with the

palaces of the lesser 32 gods arranged around it. In both Hindu and

Buddhist thought, a city so arranged becomes a representation of the

“Heaven of the Thirty-Three Gods (Pali:Tavatimsa). The chronicle claims

that Srikshetra had all the things needed for such a city: 32 main gates

and 32 small gates, moats, ditches, four-cornered towers with graduated

roofs over the gates, turrets along the walls and so forth. In later

Burmese capitals, the gates of the city represented, and were often named

after, the chief vassals or provincial governors of the realm, with the

king at the center corresponding to the celestial god Indra. The

adoption of these beliefs and their use in city planning are a good

example of how attractive Hindu-Buddhist concepts were at providing

Southeast Asians with a respected place in the cosmos and also a place in

the international Asian world.

d. Srikshetra: Architecture

Although a number of structures still exist at Srikshetra such as temples,

and stupas, there is a growing consensus among scholars that only the

stupas date to the Pyu period. The temples were most likely constructed

during the Pagan period; many for the re-installation of older Pyu images.

At Srikshetra, the ancient ruins are concentrated in the elevated southern

half of the city and also outside the fortress-like walls, while burial

mounds containing urns were found scattered throughout the area. The three

most salient monuments today are all stupas and are found outside of the

city wall: the Bawbawgyi to the south, the Pyagyi to the northwest, and

the Pyama to the north. The Bawbawgyi, the tallest of the stupas is 153

feet high and consists of a massive cylindrical column that rests on a

base of five concentric terraces. The upper portions of the main cylinder

have fallen away over time and the truncated form has been fitted with a

tower that resembles the Burmese crown or hti (hti: umbrella). It is

therefore unknown what originally crowned this monument, as well as the

other stupas at the site. However, this cylindrical stupa form that tapers

towards the top is peculiar to Burma and to Pyu culture and is believed to

represent a closed lotus bud. This form is more completely retained by the

two other important stupas at the site, the Pyama and Pyagyi. The stupa in

the form of a lotus bud can be seen in its entirety on many of the

numerous votive tablets found at the site.

|

Bawbawgyi |

Passage inside Bawbawgyi |

Votive tablet with

"lotus bud" stupas |

|

Votive tablet with

"lotus bud" stupas

|

Pyagyi Stupa, general view

|

Pyagyi Stupa, tapering side

|

|

Pyama Stupa, general view |

|

|

The Bawbawgyi is not an entirely solid structure as it may appear at first

sight. Indeed, the cylindrical body is hollow up to about two-thirds of

its height and in this regard, differs from most stupas in Burma that are

typically solid and cannot be entered. There is an opening at the base and

another aperture high up in the opposite wall. Inside the stupa was found

a small ceramic vase containing excerpts from Buddhist manuscripts that

were written in Pali (=sacred language of Buddhism) on twenty sheets of

gold and silver. The script used in writing these passages has been dated

to the mid 5th to mid 6th century AD, which dates

the structure to well within the Pyu period. Also, clay votive plaques

inscribed with the name of the first great king of Pagan, King Anawratha,

were found inside the stupa in an especially created chamber. This too is

a clear indication that the structure predates the Pagan Period and is

therefore no doubt Pyu. King Anawratha’s continued reverence for the

Bawbawgyi is bitter-sweet, however, in that when the votive tablets were

placed inside, the relics contained in the stupa were evidently looted to

be taken away to Pagan to be re-enshrined there.

The stupas at Srikshetra lack the decorative architectural moldings and

motifs that are found on modern stupas which some scholars see as an

indication of their antiquity. However, others believe the decorative

elements were originally created in plaster and they fell away long ago.

Notable in architectural features although less in height than the above

mentioned stupas are three temples, the Bebe, the Lemyethna, and the East

Zegu. The Bebe and the Lemyethna are situated outside of the surrounding

walls while the East Zegu is located inside the perimeter of the city. The

Bebe temple, made of brick, has a small square sanctuary with a porch

facing east. On top of the hollow base are three receding terraces on

which stands a plain cylindrical pinnacle with a rounded top. The

sidewalls have attached columns with false arched doorways on the exterior

and arched niches inside. A sculptured stone slab bearing a seated Buddha

flanked by a disciple on either side rests against the west wall. The

Lemyethna is a small square temple with four entrances. The core is solid

and is surrounded by a narrow corridor and four porches. Originally, each

side had a stone slab bearing a seated Buddha image. It has a terraced

roof but the pinnacle no longer exists.

Both the Bebe and the Lemyethna were made using the same building

techniques and ornamental forms that were used later in Pagan buildings.

The apparent re-installation of several Pyu images within these temples

indicates that they are obviously later constructions, thus later Pagan

Period creations.

Pointed arch and form of door-surround like those found on temples at

Pagan |

Therefore, some scholars have considered the small temples at Srikshetra

to be the prototypes for the much larger temples at Pagan. Most scholars

now accept that these temples are provincial constructions dating to the

Pagan Period and are not Pyu at all.

e. Srikshetra: Sculpture

Srikshetra, in comparison to other Pyu sites, is unusual because of the

greater number as well as complexity of the images and artifacts that have

come to light. The diversity is found not only in subject matter but in

iconography as well. Also, objects were created by a variety of techniques

and media: for example, carved stone, cast bronze, gilded repousse silver,

beaten and repousse gold, inscribed copper, engraved gems, molded and

inscribed clay. Consequently, the artistic diversity of the Pyu Period is

scarcely rivaled by later periods in Burmese history where the number of

objects available for study is vastly larger. A number of Pyu art objects

and artifacts are unique or occur only during this Period. In contrast,

objects from later periods are often repetitious so that by the nineteenth

century, Buddha images are almost always shown in a single iconographic

mode, that of “earth touching” or “calling the earth to witness”.

The sculpture from Srikshetra can be divided into categories according to

religious affiliation although the characteristics of some objects such as

Pyu coins may be equivocal. The sculpture will be discussed here according

to religion: Theravada Buddhist, Mahayanna Buddhist, Hindu, Animist and

Secular.

i.

Theravada Buddhist Sculpture at Srikshetra

Most images of the Buddha are carved in high relief with a considerable

stele backing. Several sets of these monumental images have been found

arranged so that two triads face one another. This practice occurs only

during the Pyu Period and may hearken back to the megaliths of a much

earlier time.

A

number of Buddha images were found within or outside the ancient city. A

great number of clay votive tablets have come to light as well as several

bronze molds that were used to stamp them out. These tablets were

placed in the foundation and deposit boxes of stupas and temples during

construction as a means to increase their sanctity as well as the

spiritual merit of the donor. An example of this practice is the placement

by King Anawratha of votive tablets within the Bawbawgyi stupa; each

displays fifty small images of the Buddha.

Individual images at Srikshetra represent a number of events in Gautama

Buddha’s life: The Birth, The Prince contemplating the Mysteries of Life,

Meditation, one of the most elaborate presentations of the First Sermon to

be found in Burma, Teaching with both hands in vitarka mudra, the

Enlightenment using both right and left hands for earth touching, the

earliest representation of the earth goddess in Burma in which she is

shown with two long tresses of hair, the Miracle of Double Appearances,

Overcoming the Nalagiri Elephant and Holding the alms bowl. In later

presentations these events are often assigned much less

importance and appear, if at all, within a small frame in a wall painting or

as a background embellishment to the Buddha’s enlightenment.

Gautama Buddha preaching the First Sermon |

Four earth touching Buddhas, terra cotta |

There are several remarkable depictions of the four Buddhas of the past on

silver repousse reliquaries. There are also representations of a fifth

Buddha, Maitreya, the Buddha of the Future.

Three of the identical five Buddhas of the past, stone slab from Khin Ba’s mound

|

Several bronze images believed to depict Maitreya have come to light,

although they may be the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara without his usual

identifying marks. However, one of these curious images has the name

Maitreya (incorrectly?) written on its base. The interest in Maitreya, the

Buddha as well as the Bodhisattva of the Future (like Gautama Buddha, he

is both a Theravada and Mahayanna deity), arises from a belief that he

will return to save the world. This concern with Maiteya as a savior

figure continues during the Pagan Period where it is an inspiration for

creating votive plaques and for the creation of one of the world’s rare

building types: pentagonal temples that have a shrine for each of the four

Buddhas of the Past as well as one for Maitreya.

Most sculptures at Srikshetra are typically in high relief with a heavy

stele backing, although some large single sculptures in the round have

been discovered. One such sculpture from the Kan-wet-khaung-gon mound is

made of stone and depicts the Buddha in a seated meditation posture with

two hands placed on his lap. This is a particularly important image, not

only because it is free standing but because it can be dated to the late 7th

century by the bilingual inscription on its base. The inscription is

fortunately not only in Pyu but Sanskrit as well, the script of which can

be dated. This image is then one of the few dated benchmarks that can be

used to establish a developmental chronology for Pyu sculpture.

Of particular interest is a cylindrical gilded silver casket found in the

relic chamber of the Khin Ba mound. In a style derived from the North

Indian Gupta style, it is embossed with the last four Buddhas of the

present world cycle seated in the earth-touching posture with a standing disciple

between each of them. The casket has a flat lid. A banyan tree rises from

its center that was once adorned with metal twigs

and leaves. Inscribed around the rim of the lid is a Pyu-Pali inscription

in South Indian characters. The inscription identifies each Buddha by

name as well as their disciples; it also records two names, probably of donors.

A smaller reliquary casket shaped like a cube is without a lid or base and

has a meditating Buddha seated on each face. Both reliquaries are

executed in a precise and beautiful repousse technique.

It is not possible to give a detailed description of the Pyu style of

image because so many different styles co-existed. Indeed, images that

turn up and don’t fit any of the known Burmese styles, are frequently, and

often inaccurately, dubbed “Pyu”.

ii.

Mahayanist

Sculpture

A

number of Mahayanist images appear in the assemblage of sculpture from

Srikshetra: a beautiful Avalokiteshvara, the Maitreyas mentioned

previously, and several bodhisattvas as well as female deities that at

present have not been more precisely identified.

iii. Hindu Sculpture

The Hindu images that have come to light are almost all associated with

the god Vishnu, the second member of the supreme Hindu triad, the king of

the gods, and the model for kings on earth. He is easily identified by his

major attributes the club-scepter and discus. Examples of him standing on

the shoulders of his winged mount, Garuda, with a female goddess have been

uncovered. Several representations of Vishnu reclining on Ananta, his

loyal serpent-protector have been found not only at Srikshetra but in the

Mon countries as well. A truly extraordinary image, long identified as a

guardian figure or devarapala has recently been identified as a standing

Garuda, - perhaps with Tantric associations.

Several secular figures have also come to light. An exceptionally fine

collection of bronze figures was discovered in an excavation near the

Pyama stupa. Five bronze Buddhas along with five animated figures that

together constitute a wandering troupe of entertainers: a flute player, a

drummer, a cymbalist, and a dancer, along with what seem to be a dwarf

clown carrying a sack. All of the figures in the troupe are beautifully

cast although they are all less than four and one half inches tall.

A

truly enigmatic two-faced stele was discovered that is thought to depict a

warrior king accompanied by his two lieutenants. On the reverse, two women

- the king’s wives? - hold an empty throne awaiting the king’s arrival.

If the recent identification is correct, it is a representation unique

within the history of Burmese art.

Also of interest is an ornately molded bronze bell that measures eleven

inches in height and is decorated with two emblems of srivatsa, a symbol

that frequently appears on Pyu coins.

f. Srikshetra: other arts

Small objects and statuettes made of gold, silver, and copper have also

been found at Srikshetra. Such objects include miniature stupas of silver,

gold and silver caskets, models of boats, ducks, deer, butterflies, lotus

flowers, gold and silver rings, necklace of elephants made of jade, and a

variety of beads made of carnelian, amethyst, crystal, quartz, agate, and

glass.

i.

Animist Arts

Earthenware funerary urns of varying shapes and sizes were found while

excavating mounds scattered throughout the city and its environs. Most of

the urns contain calcified bones mixed with ashes and loose earth. The few

copper and stone urns that have been found were probably used for the

burials of royalty. This was almost certainly the case because the four

large stone urns that were discovered near the Payagyi pagoda each bear a

brief epitaph recording the names of royalty and their dates.

|

Inscribed Stone Urn, side view |

Inscribed Stone Urn, top or inside view |

Inscribed Stone Urn with lid |

|

Inscribed Stone Urn without lid |

Inscription on base of Urn |

Inscription on side of Urn |

The use of urns, both stone and ceramic, for secondary burial is a

widespread trait in early Southeast Asia. Their use during the Pyu Period

is probably the continuation of an earlier megalithic practice.

E. Pyu City States: Conclusion

What little is known concerning the decline of the Pyus comes only from

Chinese sources which claim that invasions in the ninth century from

Yunnan province in China occupied areas that had once belonged to the Pyus.

One Chinese chronicle refers to the defeat of the Pyus and the capture of

three thousand residents from what was probably Halin. However, there are

no firm indications at Srikshetra or at any other Pyu site that suggests a

violent overthrow. These incursions are thought to have weakened the

Pyu

State so that by the ninth century the Burmese were able to move down into

what had been Pyu territory and settle in Kyaukse and the Pagan region.

The Pyus left their mark on the Pagan State; in as much as the site of

Srikshetra was incorporated into the state ideology. The first kings at

Pagan traced their mythical genealogy back to the kings of Srikshetra, a

continuity in political life that is not found elsewhere in

Southeast Asia. On

balance, however, a considerable gap exists between the fall of the Pyus

in the ninth and the earliest datable Pagan shines to the 11th

for the Pyus to have played an important part in creating the artistic and

cultural life of Pagan.

The Pre-Pagan Period: The Mon and Pyu

City States -Bibliography

Aung Thaw, Excavations at Beikthano (Rangoon, Ministry of Union

Culture, 1968).

Aung Thaw, Historical Sites in

Burma

(Rangoon, Ministry of Union Culture, 1972).

Michael Aung Thwin, “Burma Before Pagan: The Status of Archeology Today”,

Asian Perspectives, XXV, (1982-83), pp. 121. [Published 1988]

John Guy, “The Art of the Pyu and the Mon” in Donald Stadner, ed., The

Art of

Burma, New Studies

(Mumbai, Marg Publications, 1999), pp. 13-28.

G. H. Luce, Phases of Pre Pagan Burma (Oxford, 1985), vol.1 & 2.

Donald Stadner, “The Art of Burma” in Maud Girard-Geslan…[et al.], The

Art of Southeast Asia (New York,

Harry N. Abrams, 1997), pp.39-92.

Janice Stargardt, The Ancient Pyu of

Burma,

Vol. I (Cambridge and Singapore, PACSEA and ISEAS, 1990).

Paul Wheatley, Nagara and Commandery: Origins of the Southeast Asian

Urban Traditions (Chicago, 1983).

Robert S. Wicks, “The Ancient Coinage of Mainland Southeast Asia,

Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, XVI, no. 2 (September 1985), pp.

195-217.

Robert S. Wicks, Money, Markets, and Trade in Early

Southeast Asia: The

Development of Indigenous Monetary Systems to AD 1400

(Ithaca, Cornell University Southeast Asia Program, 1992). |