|

The Post

Pagan Period

- 14th To

20th Centuries

Part 1

A. Introduction and History

The decline of Pagan as a political center in the 13th

century led to almost three centuries of internecine warfare and internal

division. The former Pagan kingdom was repeatedly divided among rivals and

only rarely was central Burma administered from a single center. Several

competing kingdoms arose, ruled for relatively short periods to be

eclipsed by their adversaries who typically plundered the capitol,

destroyed religious buildings, burned written records, and led the

population away as captives to the new center of power. Additionally,

severe earthquakes damaged or destroyed the few buildings left standing,

particularly during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Therefore, a

great abundance of visual material has not survived from the 14th

through 18th centuries.

From the materials available, it is apparent that after the 13th

century most forms in art and architecture continued those of the Pagan

Period rather than expressing new approaches and concepts. Indianized

forms fell from favor and continued to be replaced by those of indigenous

Burmese inspiration. The arts of the Post Pagan period express nostalgia

for the glory of the Pagan. The Shweizigon stupa and the Ananda temple

were copied in creating new capitols as a means of validating the aspiring

king’s claim to the throne. Also, kings from distant kingdoms returned to

Pagan to refurbish ancient structures, to complete wall paintings or,

occasionally, to build new buildings. Many new stupas were built and

ancient, revered examples were enlarged and repaired. Temples, however,

became a conscious anachronism. On the few temples that were constructed,

a stupa-like finial or a multi-tiered, square pavilion, the Burmese

payattat, replaced the shikhara tower often seen on the great temples at

Pagan.

Burmese art history after the Pagan Period has traditionally been

divided into segments that employ the name of the then dominant kingdom

such as the Pinya Period (14th century), the First Ava Period

(15th century), the Toungoo and second Ava Periods (16th

century), the Nyaungyan Period (17th century) and the Konbaung

Period (18th to 19th centuries). These divisions are

not particularly useful in discussing the arts because styles often

continued unchanged from one period to another, several styles were

produced simultaneously, and innovations were not necessarily repeated,

even during the era of their initiation. Therefore, this review of the

development of Burmese arts after the Pagan Period will be divided into

two long periods in which various innovations will be discussed

chronologically: The Ava Period (c. 1287-1752) and the Konbaung Period

(1752-1885)

B. The Ava Period c. 1287 –1752 AD

1.Introduction

The city of Ava was established in 1364 at the confluence of the

Irrawaddy and the Myitnge rivers, a site of considerable economic

importance because it was the gateway to the vast irrigated rice fields of

Kyaukse that lay south of the Irrawaddy and were drained by the Myitnge.

Kyaukse had been first settled and developed by the Burmese prior to the

Pagan Period. Since it was the economic base for upper Burma as well as

the Burmese homeland, control of this area was of particular concern to

the Burmese kings. Consequently, many of the post Pagan capitols in Upper

Burma were located in this area on either side of the major westward bend

of the Irrawaddy. Importantly, the Sagaign hills, just northwest of the

bend, became an important location for monastic communities, a great

center of Buddhist learning that also offered the possibility of sanctuary

to townsmen in case of attack.

Ava did not officially become a capitol of the Burmese kingdom

until1636 and it was not until the period between 1597 and 1626 that it

controlled the major part of Burma. None the less, the capitol was

repeatedly established there and until modern times Burma was often

referred to by the outside world as Ava. Its official name was Ratanapura,

the City of Gems, and several foreign visitors have written of its wealth

and splendor. Ava was almost completely destroyed by earthquake in 1838,

and was finally abandoned in 1841 when King Shwebo Min moved the capitol a

short distance east to Amarapura.

Engraving of the Royal Palace in

Ava

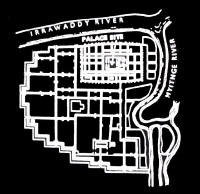

2. The City Plan of Ava

The city of Ava was established on an island that was created by

connecting the Irrawaddy on the north and the Myitnge on the east with a

canal on the south and the west. The brick fortifications of Ava do not

follow the conventions of the earlier rectilinear city plans. Instead, the

zigzagged outer walls are popularly thought to outline the figure of a seated lion. The inner

enclosure or citadel was laid out according to traditional cosmological

principles and provided the requisite twelve gates. The inner city was

reconstructed on at least three occasions in 1597, 1763, and 1832.

City Plan of Ava

3. Architecture

Buildings constructed during the Ava Period perpetuate the "Burmese"

types of stupa, temple, and monastery that had evolved at Pagan. However,

in comparison to the interest in building and renovating stupas, very few

temples were erected.

a. Temples

There is little that remains of any monuments from the early Ava Period.

One of the few structures that still stand within the walls of Ava is

the Leidatgyi temple that dates from the seventeenth century. Although it

was severely damaged by an earthquake in 1839, it is obvious from its

double fenestration, radial vaulting, the design of its elaborate stucco

work and the seated lions above the main portal that it was intended to be

a copy of the Ananda temple at Pagan.

Slide: Leidatgyi Temple, Ava

- to be added Spring 2003

b. Stupas

Many large stupas were regularly built during the Ava Period although

large temples seem to have fallen from favor. Also, older revered stupas

were often repeatedly enlarged and reconstructed. Among them is the

Htilainshin Stupa in Ava that was built by the great Pagan King Kyanzittha

although its present shape is the cumulative result of many later repairs

and additions. Renovation and refurbishment became so widespread at this

time that the most revered stupas in Burma were transformed into their

present shape, even if the outer surfaces have been more recently

reworked. This includes the Shwedagon in Rangoon, the Shwesandaw in Prome

and the Shwemawdaw in Pegu.

Shwemadaw Stupa, Pegu, Late 18th century

engraving

Stupas during the Ava Period continued the Pagan model although there

were changes in proportion and detail as well as the occasional

innovation. The pervasive trend was to merge the separate elements of the

Pagan model into a continuous conical profile. This was accomplished by

multiplying the number of small stepped tiers between the ground and the

base of the bell and by giving an inclined outline to the lower terraces.

This change became so pervasive that in more recent stupas the shoulder of

the bell and its concave face were suborned to the overall conical shape.

The Htupayon Stupa in Sagaing, begun in approximately 1460 but never

finished, retains the bell-shaped dome of the Pagan period. The rows of

niches, however, that occur in all three of its circular terraces are an

innovation.

Although the Kaunghmudaw Stupa was created in 1636 to commemorate the

establishment of Ava as the royal capitol, it is located across the

Irrawaddy from the city, about six miles northwest of Sagaing. One of the

largest and most unusual stupas to be built during the Ava Period, its

broad, hemispherical, lotus bud-like dome set upon three, circular

terraces is a copy of the famous Mahaceti Stupa in Sri Lanka. The huge

dome measures 151 feet in height and 900 feet in circumference. Only the

lowest terrace of the stupa has niches and each of these was filled with

one of 120 images of spirits (nats) or gods (devas). Another innovation is

found in the ring of 812 stone pillars, measuring five feet high, that

encircle the base, each having a niche to hold an oil lamp. In late

October lamps are placed in each column for the annual Thadingyut Light

Festival that marks the end of Buddhist lent.

Kaungmudaw Stupa

c. Monasteries

The Pagan monastery types constructed of brick and stucco were not

continued after the fourteenth century. Although there are numerous

written records recording the construction of wooden monasteries during

the Ava Period, little remains today of these early structures that were built of

perishable materials.

4. Sculpture

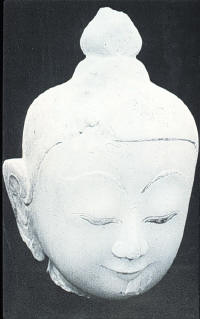

a. The Ava Style Image

During the Ava Period there were fewer contacts with India and

consequently several particularly Burmese image styles evolved. The

typical Ava image was made of marble and was carved completely in the

round. The stele backing so often used at Pagan is rarely seen. The full

and fleshy body is seated on a lotus throne with legs entwined in the

lotus position with the right hand calling the earth to witness (bhumisparsa

mudra). The squarish head has full cheeks and a fig-like finial above the

low usnisha. The ears curve slightly outward and stretch down to touch the

shoulder. A small, thin lipped, puckered mouth is situated just below the

long, broad nose. The eyebrows arch dramatically upward approximating a

semi-circle that may be incised and painted. The half-closed eyes look

down instead of outward and in some images the features seem extremely

child-like. This curious countenance is explained by the Burmese as a way

of indicating that the Buddha manifested the purity of an infant. The

fingers and toes are most often all the same length. Supporting props of

marble may appear between the thumb and the index finger of the same hand

or under the hand or wrist.

Drawing of Buddha Head, Ava Style – 17th

century |

Marble Buddha Image, Ava Style - 17th

century |

Marble Buddha Head, Ava Style - 17th

century |

Bronze image, inscribed 1628 |

Wooden Buddha image, dated 1640 |

|

b. The Jambupati Image

According to accepted Theravada Buddhist practice, images of Gautama

Buddha appear clothed in unadorned monk’s robes with his hair in small

curls and his body devoid of jewelry. The continuity of this visual

convention is emblematic of his renunciation of this would of desire and

is a reminder of his having sacrificed his material heritage as a crown

prince.

In marked contrast to this strong tradition, there is a cultist

convention in Southeast Asia, which depicts the Buddha in lavish royal

attire and is known as Jambupati Buddha. One possible explanation for this

convention derives from the meeting of the Buddha with King Jambupati. The

haughty King Jambupati lived during the time of the Buddha and with his

boundless power, he terrorized the world. The Buddha requested that

Jambupati forsake evil and practice kindness, but Jambupati was not moved.

Realizing the king’s total reluctance, the Buddha magically appeared in

resplendent royal raiment that so awed Jambupati that he accepted the

Buddhist precepts. In Southeast Asian countries like Burma, where rulers

have very high if not semi-divine status, tales of this type justify the

need for the king to worship the Buddha, the King of Kings.

Jambupati image, Ava

Style |

Jambupati

image, Ava Style |

5. Painting

Ava Paintings continued the major religious themes and

subject matter of the Pagan Period while the settings were given a

local context that included contemporary Burmese architecture, dress,

hair-styles, and jewelry as well as local flora and fauna. Scenes from

everyday life included not only court life and palace scenes but commoners

involved in daily activities such as fishing, plowing or making ceramic

pots.

There was a change in format away from small, neatly divided panels to

long registers that allowed for the inclusion of more figures,

particularly of subordinate characters or figures unrelated to the

narrative. The last ten Jatakas were most favored and were presented more

completely in great detail, at times a single Jataka covering an entire

wall.

The Ananda Ot Kyaung, Exterior |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung,

Interior Corridor |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung,

Wall Painting |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung,

Court Scene |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung,

Rider on elephant |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung,

Conversation |

The Ananda Ot Kyaung, Garuda |

|

New pigments were introduced such as bright reds, yellows, blues but

especially turquoise that produced richer more vivid paintings as seen in

the Tilawkaguru Meditation caves (1672) in Sagaing and the Ananda Brick

Monastery (Ananda Ot Kyaung) and the U Pali Ordination Hall (Thein) in

Pagan.

Tilawkaguru

Cave Monastery, Exterior |

Tilawkaguru

Cave Monastery, Scene in Royal Palace |

Tilawkaguru

Cave Monastery, The Great tonsure, Two seated Buddha |

Tilawkaguru

Cave Monastery, The Birth of the Buddha

|

<Next>

<Table of Contents> |