|

The Post

Pagan Period

- 14th To

20th Centuries

Part 3

D. Mandalay Peroid

1. Introduction

Although Mandalay was the capital of Burma for only a brief period of

25 years (1860-1885), it was here during the reign of King Mindon that the

arts of Burma came to their final flowering. By 1852, as a consequence of

the First (1824-26) and Second (1852) Anglo-Burmese Wars, Britain had

gained control over the lower half of the country which left Mandalay and

Upper Burma completely cut off from the coast and the outside world. Many

believed that only divine intervention could save Burma from being

entirely conquered by Great Britain.

To assure purity and consequent strength and prosperity, King Mindon

moved the capital from Amarapura to a new site a few miles to the north of

the old capital at the base of a sacred hill. Tradition maintains that

Gautama Buddha visited the sacred peak of Mandalay Hill with his disciple

Ananda, and proclaimed that on the 2400th anniversary of his

death, a metropolis of Buddhist learning would be founded on the plain

below

the hill. In this way, the shift of capitols was justified, and a standing

image of Gautama Buddha pointing to King Mindon’s palace was subsequently

erected on Mandalay Hill.

The political center of the new city had the perfect geometrical form of a

Buddhist Mandala, for which the city was named, Mandalay. Despite British

control of the lower third of the country, King Mindon arranged for a

remarkable International Buddhist Council to be held at his new capital,

only the fifth such council or synod to be convened since the Buddha’s

death in the 6th century BC! The King constructed a number of

buildings in which to convene the synod and to welcome the delegate monks

who arrived from throughout the Buddhist world. Among these were the

Kyauktawgyi Temple at the foot of Mandalay Hill (1878), the Kuthawdawgyi

Stupa and the Atumashi monastery and assembly halls.

His mission in convening the Synod was to purify the clergy by

standardizing the Pali scriptures – a traditional undertaking of great

Theravada monarchs. At King Mindon’s command, 2,400 monks were assembled

in the eastern hall of the palace to work on this project that required

five months to complete. The completion of the synod was celebrated by the

installation of a new hti atop the Shwedagon Stupa in Rangoon, then

located in British held territory.

Although the king’s actions produced extraordinary art and

architecture, they were to no avail against the British military forces.

In 1886, Mandalay and Upper Burma fell to the British at the conclusion of

the Third Anglo-Burmese War and the last Burmese king, King Thibaw, was

exiled to India.

Fortunately, the Royal Guilds who created such exceptional works for

the King remained in Mandalay where they have continued until today to

produce art objects in the Mandalay style. Gold was thought to represent

the radiance of spiritual energy and power and was all that King Mindon

had to muster as the British gunboats came progressively closer to

Mandalay. Gold, therefore, played an important part in the Mandalay Style

that is characterized by the extensive use of gold leaf with bits of

inlaid colored glass and silver mirror – a style seen to best advantage in

the relatively dark interiors of the palace and monasteries.

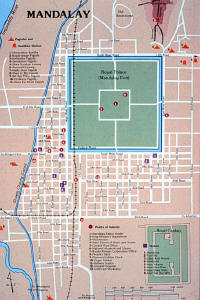

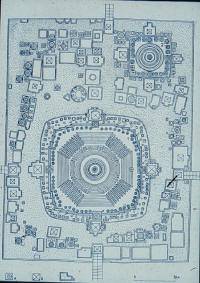

Map of Mandalay

2. City Plan of Mandalay

At the center of Mandalay was a massive square brick wall that measured

a mile and one eighth (7 furlongs) on each side. This crenellated wall

rose to 25 feet and was backed by an earthen rampart. There were twelve

gates, three evenly spaced along each side. Each gate was surmounted by a

square wooden pavilion, a pyatthat, and marked with a sign of the zodiac.

This fortress was completed by a wide moat that averaged 225 feet in width

and 11feet in depth. Consequently, in modern times this fortification has

often been referred to as Mandalay Fort. The wall, however, was built not

only to provide security but also to demarcate a sacred space for the

royal palace that was situated at the very center of its three concentric

enclosures. The homes of commoners and foreigners, shops and workshops,

and the markets were located beyond the wall along a rectilinear grid of

streets that also had the palace compound as its symbolic center.

Mandalay Wall and moat, with payatthats

over gates |

Payatthat

at South Corner of fort wall |

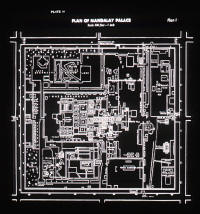

3. The Mandalay Palace

The plan of the royal palace in Mandalay is typical in many ways of the

royal palaces found throughout Southeast Asia. It consisted of groups of

wooden buildings erected on a masonry platform within a secure enclosure.

All of these structures were one-storey buildings with teak floors and

multiple roofs held in place by tall wooden columns.

Because the palaces were important objectives in times of war and were

made of perishable material, most have disappeared and are known in detail

only from contemporary paintings, descriptions in chronicles, or from

traveler’s accounts. The Mandalay Palace, constructed in 1857 from the

disassembled palace at Amarapura, is the last example of this long

tradition. Even though all the palace buildings were destroyed during

World War II, they are well document by photographs and in architectural

surveys.

Inside the fortified brick wall was located two additional square

enclosures. The first consisted of a teak stockade and brick wall inside

of which were arranged formal gardens and groves of trees around ponds and

canals. At the center of this enclosure were a low boundary wall and the

rectangular palace platform that enclosed an area measuring 400 meters by

210 meters. All the palace buildings were erected on this platform that

stood six feet tall and could be accessed by several stairways. The

primary entrance was in the middle of the eastern façade, which was the

beginning of an east-west axis along which all major buildings were

arranged.

The most important building along the eastern front of the palace was

the Great Hall of Audience that consisted of a large, central throne room

with two open, lateral wings to accommodate large gatherings. Immediately

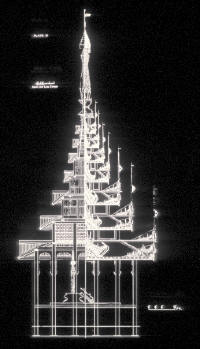

behind this building was the Hall of the Lion Throne where the most

important ceremonies of state were performed. Since this building was

considered the center of the universe, it was marked by the tallest tower

within the complex that soared upward though seven tiers to 256 feet. Each

of the eight throne halls was known by the animal or insect that was used

in the decoration of its throne.

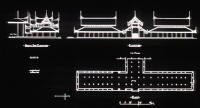

Each throne hall consisted of a rectangular room that was divided in

the center by a partition wall in which there was a doorway that opened on

top of a high pedestal into the front half of the room. The King’s ascent

to the throne was by a short stair in the "back" half of the room that led

up to the door. After passing through the door, the king sat atop the

pedestal and looked down upon his subjects who lay prostrate below him on

the teak floor.

Ground Plan of Mandalay Palace |

East Elevation of Mandalay Palace |

South Elevation of Mandlay

Palace |

The Great Hall of Audience |

The Lion Throne |

Payatthat

spire over Lion Throne |

The Hamsa

(Goose) Throne |

Cross section of Palace Construction |

Exterior

of the Glass Palace |

Other buildings such as the royal sleeping quarters, the treasury, the

armory, a theatre and recreation rooms, an elegant watch tower, the

servants and soldiers quarters, stables, and elephant shed were placed on

either side of the Throne Halls or at the periphery of the compound.

During the Konbaung period, throne halls so closely resembled the main

hall within a monastery that when King Mindon died in his palace apartment

in 1880, it was disassembled and reconstructed outside the palace walls

where it has continued to be used as a monastery building. It is now known

as the Golden Monastery or Shwenandaw.

4. Architecture – Temples

a. The Kyawktawgyi Temple, Mandalay

In 1853 King Mindon began construction of the Kyawktawgyi Temple at the

foot of the southern stairway to Mandalay Hill. Although the temple was

modeled on the Ananda Temple at Pagan, it contained only a single enormous

seated image of the Buddha when finished in1878. This, however, had been

carved from a gigantic block of white marble that had taken 10,000 men to

transport the stone from the Irrawaddy to the temple site. This is the

largest stone image of the Buddha in Burma. An innovative feature of the

temple not found at the Ananda or elsewhere was the inclusion of marble

images of the Buddha’s eighty-eight disciples in large niches in the

compound wall.

Image within the Kyawktawgyi Temple, Mandalay

- to be added Spring 2003

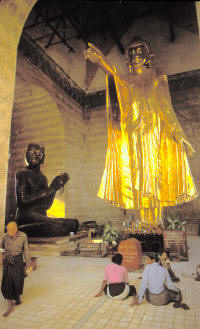

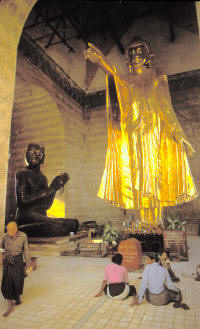

b. The Shweyattaw Temple

The Shweyattaw temple was built by King Mindon approximately half way up the southern

approach to Mandalay Hill. to house an enormous standing image of Gautama

Buddha that dramatically points to the royal palace on the plain below -

the reification of the Buddha’s prophecy that a great Buddhist metropolis

would appear there. The building is of interest because the names of

Burmese lay donors cover the interior walls.

The Buddha with disciple Ananda, The Shweyattaw

Temple, Mandalay Hill

5. Architecture - Stupas

a. The Kuthawdaw Stupa Complex

The stupa at the center of the Kuthawdaw complex, the Mahalawka

Marazein, is also a distant copy of the Shwezigon stupa at Pagan although

generally much smaller in size. Filling the large compound around the

stupa are 729 stupa shrines that each contain a marble tablet on which,

for the first time, the entire Tripitaka was inscribed in Pali script.

This text was prepared for inscription by 2,400 monks during an

International Buddhist Synod that King Mindon convened in Mandalay in

1872. The complex is often referred to as "the world’s largest book" and

is most impressive when seen from Mandalay Hill.

The Kuthawdaw Stupa |

The small shrines, each containing

a "page"of the Tripitaka |

b. The Sandamuni Complex

The Sandamuni Stupa, a complex very similar to the Kuthwdaw, was built

adjacent to its neighbor in 1866 by King Mindon. The central stupa,

erected over the burial place of the King’s younger brother, is encircled

by 1,774 stone tablets that record commentaries on the Tripitaka – an

addition credited to the remarkable hermit of Mandalay Hill, U Kanti.

Slide: The Sandamuni complex

- to be added Spring 2003

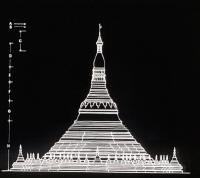

c. The Shwedagon, Rangoon

According to legend, the Shwedagon was first created as a repository

for eight hairs from the Buddha’s head that had been given to two merchant

brothers, Tapussa and Bhallika, who had gone to India from Okkala village,

now Rangoon, to worship the Buddha. If true, the Shwedagon would have been

founded in the 5th century BC while the Buddha was still

living. King Anawratha is reputed to have visited the Shwedagon during his

military campaign to the south and had to be dissuaded from taking its

hair relics back to Pagan. The earliest reliable records report that the

stupa was renovated in 1372 by King Byinya U and again fifty years later

by King Binnyagyan who raised the height of the stupa to 295 feet. The

present shape and form of the stupa is the result of donations made by

Queen Shin Sawbu who ruled from 1453-1472 and gave her weight in gold, 90

pounds, to be used to plate the exterior of the stupa. Earthquakes damaged

the structure several times in the 17th and 18th

centuries and it was again repaired. The Konbaung king Hsinbyushin

replaced the hti in 1774, thus raising the monument to its present height

of 330 feet.

The stupa was built on the crest of a large hill, the top of which was

leveled to create a spacious square plaza. This area was walled and, over

time, has become progressively filled with numerous lesser shrines and

buildings that ring the base of the main monument. The plaza is reached by

four covered stairways that pass through the center of each wall.

Drawing of Elevation |

Ground Plan |

General View |

The Promenade Circuit |

General View |

Smaller shrines at base of Stupa |

Each staircase opens onto the promenade circuit that connects the four

major shrines, which are situated at the base of the stupa. Each of these

shrines contain a number of virtually identical, Mandalay style Buddha

images that are the major focus of worship.

The form of the Shwezigon is one of the most complex in Burma. Inside

the circular promenade course and above the main platform is a massive,

square plinth terrace over 20 feet high that holds 68 small stupas. This

area is used by men for meditation. A series of narrow terraces that

progressively change in shape from square to octagonal to circular create

a smooth transition from the square base to the dominant circular bell.

Above the bell, the most highly ornamented section of the stupa consists

of rings of lotus petals. Above these rings is a tapering section that

resembles a lotus bud. A thirty-foot, gem-encrusted hti adorns the top of

the lotus bud and this is crested by a gem-covered vane and orb.

The profile of the monument closely approximates that of a regular and

continuous cone and has become the emblem of Burmese Buddhism today.

6. Monasteries

a. Introduction to the wooden Monastery, a unique Burmese type

The brick monasteries of the Pagan Period were not built after the 14th

century.

Instead, wooden monasteries appeared in great numbers throughout

central Burma that are particularly Burmese in design. These structures

were often of great size, some measuring up to 250 feet long by 45 feet

wide.

This monastery type is raised on pilings and consists of a single, long

building having several rooms that rest on a wooden platform, which

extends outward from the exterior walls, thus creating a terrace around

the entire structure.

Massive staircases made of brick and stucco give access to the main

platform and serve to buttress the super-structure that was made entirely

of wood.

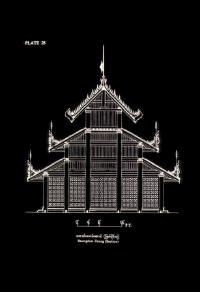

Engraving of Monastery at Ava, 18th century-from

Symes |

Elevation & ground plan for Shwe Inbin

Monastery, Mandalay |

Brick and Stucco stair to terrace, Shwe Kyaung,

Mandalay |

Raised terrace between main buiding and terrace railing, Shwe

Kyaung |

Interior of Main Building, Shwe Kyaung,

Mandalay |

Elaborately carved roof, Shwe Kyaung,

Mandalay |

Typical Roof Corner, Wooden monastrey,

Mandalay |

|

The monastery building itself had several rooms or spaces that were in

linear alignment from east to west. The first room is a room where Buddha

images and sacred texts are stored and, at times, informally displayed.

This important space is marked by a tall tower and is linked to the main

hall by a transitional, lower space where the head monk resides.

The most important part of the building is located at its symbolic

center and is a large rectangular hall divided into two square rooms by a

partitioning wall. The room nearest the eastern entrance is a public space

where a Buddha image is displayed and rituals involving both monks and

laymen are celebrated. The western room is reserved for activities in

which only monks are involved. To the West beyond the main hall, a

storeroom is situated that may be attached or unattached to the main

structure.

The entire structure is visually unified by the continuous horizontal

terraces and eaves of the various roofs.

The exterior walls of the monastery as well as the terraces were

lavishly decorated with wood carving often depicting Jataka tales in high

relief. The multiple levels of the roof were also profusely adorned with

fine carvings of flora, fauna, minor deities and humans.

7. Sculpture

a. Introduction

Of the several styles of sculpture that were produced during the

Konbaung Period, the Mandalay style became dominant and has persisted

until the present day.

Drawing of head in the Mandalay

Style |

Seated Buddha Image, Mandalay Style |

Seated Buddha Image, Mandalay Style |

Seated Buddha Image, Mandalay Style |

Seated Buddha Image, bronze, Mandalay Style |

|

During the Konbaung Period there is a marked preference for stone and

wood, although Mandalay style images were also made in metal. The most

favored image in the Mandalay style is a seated Buddha in the position of

calling the earth to witness, of which thousands were created. There was

also a renewed interest in standing images, many of which are shown

holding in their right hand a myrobalan fruit, a symbol for spiritual and

physical healing. The left hand of these standing images often grasps the

edge of the outer robe to hold it open. In other standing images, both

hands are used to hold the outer robe open. Images of the reclining Buddha

depicting the Parinirvana, also appear but in much fewer numbers than the

other two body positions. Among the representations of Parinirvana, there

is a new relaxed presentation where the Buddha’s feet are casually

arranged rather than being stacked atop one another. Unfortunately, these

images often create an impression that the Buddha is facing a television

set, instead of death.

Reclining Buddha, Mandalay Style |

Reclining Buddha, Mandalay Style, Shwedagon Stupa |

Images in the Mandalay style have full, fleshy bodies with some slight

difference in the length of the fingers and toes. The head is a broad oval

in which the features arranged horizontally. A wide band, often inlaid

with faux gems, borders the forehead and resembles a jeweled tiara. Small

black curls cover a full usnisha that rarely terminates in a finial. The

mark on the forehead, the urna, may have the spiral form of an "om"

symbol. The eye brows are lower and more naturalistic, the mouth broader

and more naturally smiling than those of Ava Period images. The ears are

long, curve slightly and may touch the shoulders. The contours of the body

are almost completely lost under heavy robes that are deeply undercut and

have undulating hems inset with ornate bands of faux gems.

Standing image of the Buddha |

Standing image of the Buddha

|

b. Examples of the Mandalay Style

The Shweyattaw image of a standing Buddha pointing with his right

hand is an iconic innovation of the Mandalay Period that is not found

elsewhere in Burma or elsewhere in the Buddhist world. A limited number of

small replicas were produced, evidently as souvenirs for pilgrims to the

Shweyattaw temple since there is no known ritual use for these peculiar

images.

The Shweyattaw Image

8. Painting and Prints

a. Painting

During the Konbaung Period, the number of foreigners who visited Burma

increased and several artists and architects settled in the capital

cities. These individuals as well as the increased availability of printed

materials, encouraged the use of western perspective and the adoption of

western modes of painting such as landscape and portraiture that were

intended for the home instead of the temple or monastery. The paintings in

the entrance halls of the Taungthaman Kyauktawgyi are a good example of

the adoption of western perspective in creating a scene that fills the

wall from horizon to zenith of the heavens. Cast shadows and distant

haziness are used to enhance the illusion of reality. The stupas in the

wall paintings are meant to be recoginizable pictures of stupas within the

kingdom that the king had built or refurbished.

Wall painting of Stupa and Burmese house that along with sky is

a continuous idealized landscape, Taungthaman Kyaukthawgyi, Mandalay |

Wall painting of Stupa using single point perspective,

Taungthaman Kyauktawgyi, Mandalay |

Wall painting of figures in Stupa compound, Taungthaman

Kyauktawgyi, Mandalay |

Typical Burmese house with woven walls, Taungthaman Kyauktawgyi |

Footprints of the Buddha, Images of Rahu – Lord of the Eclipse,

and consellations, ceiling painting, Taungthaman Kyaukthawgyi, Mandalay

|

U Pali Thein Ordination Hall, Exterior View, c. 1794, Pagan |

U Pali Thein, Interior View, East end, c. 1794, Pagan |

U Pali Thein, Interior View, West end, c. 1794, Pagan |

U Pali Thein, Wall Painting of devotees, c. 1794, Pagan |

U Pali Thein, Wall Painting of Flying deva, c. 1794, Pagan |

|

|

b .Prints

British Officers who served in Burma during the First Anglo-Burmese War

(1824-1826) often made sketches of the scenery and countryside as part of

the Search for the Picturesque, a pursuit then fashionable in England. The

best drawings were reproduced in England as aquatint prints, many of which

were then sent back to Southeast Asia to those who had requested them. Two

print series consisting of twenty eight views chronicle the progress of

the war and, remarkably, only seven scenes depict military action,

considering that the artists were British officers. These prints

constitute the first series of naturalistic landscapes in the history of

Burma and, even if they are not absolutely accurate in a photographic

sense, the prints are the first large-scale, colored views of the Burmese

landscape.

The twenty-eight aquatints were executed from drawings made "on the

spot" by two officers of the British Expeditionary Force in Burma, Captain

James Kershaw and Lieutenant Joseph Moore. Although little is known about

these officers, their work is exemplary of the fashionable pursuit of the

picturesque.

In an historical sense these prints do not accurately reflect the

realities of a disastrous war which resulted from the combatants having

only a vague notion of the aims and abilities of each other. However, the

prints are of aesthetic interest because the circumstances of their origin

are a direct outgrowth of the enormous interests in the picturesque that

existed at this time, both in England and her colonies.

The dichotomy seen here between picturesque fantasy and the reality of

the war is a direct result of the strong British commitment to the Cult of

the Picturesque which was one aspect of the Romantic Movement.

Unfortunately, the failure to grapple with reality extended to the

organization of the war which was undertaken from India and, because vital

logistic information was lacking, resulted in heavy British losses from

disease.

The isolation of the Burmese Court at Ava about 300 miles inland helped

create a false sense of security for the Burmese which increased their

vulnerability to British military superiority, and thus assured a

disastrous outcome to the war.

The Cult of the Picturesque

Although the search for the picturesque in England and abroad was as

much the province of the amateur as the professional artist, it was not to

be causally approached. One writer, more insistent than most, on what

might constitute a true rendition of the Picturesque was William Gilpin

whose Three Essays on the Picturesque are specific as to the composition

of landscape and subjects which will achieve the desired effect. His

advice for sketching landscape proposed a clear delineation between the

foreground, midground and background.

The foreground might contain trees, tangled vegetation, and mossy

stones, all loosely arranged to frame the midview. The midground in which

increased depth recession creates expansive vistas holds the viewer’s

interest with a variety of forms which delightfully distract the eye. The

subtle tones that create these atmospheric vistas were readily produce by

the aquatint technique. The misty blue-grey background halts the eye and

teases the imagination about what view might lie beyond.

The entire composition should be enlivened by variety, intricacy, and

visual incident of imprecise detail. These effects may be further enhanced

by changes in form, hue, and texture. Gilpin concludes that a figure or

two may be introduced with propriety. The atmospheric power of the print

was increased with the inclusion of turbulent skies, which gave the

watercolorist and engraver an opportunity to increase the quality of

"roughness" in a picture.

The Cult of the Picturesque acknowledged that merely to enjoy a scene

once was insufficient. Every attempt should be made to record the

experience to renew it at leisure. Gilpin further suggests that even

greater pleasure might result from contemplating the recorded scenes when

relaxing at home, far from the wild and savage parts of nature.

Paul Sanby introduced aquatint engraving to England in 1775. The new

technique enabled much greater atmospheric variety to be achieved by

insuring that the delicate shading of the fashionable watercolors be

retained. This insured that even the multiple images of a plate would not

decrease the beauty and subtlety of the original work. Theodore Fielding

described the technique as an art which is so beautiful, yet so difficult,

so peculiarly adapted to those subjects requiring broad flat tints of

extreme delicacy or excessive depth, so capable of expressing light

foliage on a dark background and the only style of engraving which can

faithfully render the touch of the artist’s brush.

Although the outcome of the war is now a matter of historical fact, the

prints continue to excite the senses - and those prints that most

inventively embody the formula for the picturesque still yield the

greatest satisfaction.

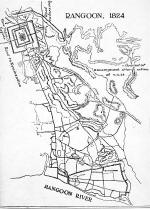

Map of Rangoon in 1824 |

Engraved frontispiece to the Print Portfolio |

J. Moore. "The

Harbour of Port Cornwallis, Island of Grand Andaman, with the Fleet

getting under Weigh for Rangoon" |

J Moore. "View

of the Landing at Rangoon of Part of the Combined Forces from Bengal

and Madras" |

J. Kershaw.

"Rangoon from Anchorage" |

J. Moore. "View

of the Great Dagon Pagoda and adjacent scenery on the Eastern Road

from Rangoon" |

J. Kershaw.

"Dagon Pagoda, near Rangoon" |

J Moore. "View

of the Great Dagon Pagoda at Rangoon and scenery adjacent/to the

Westward of the Great Road" |

J. Moore. "The

Principle approach to the Great Dagon Pagoda at Rangoon" |

J. Kershaw.

"Dagon Pagoda near Rangoon" |

J. Moore. "Scene upon the Terrace of the Great Dagon Pagoda at

Rangoon/Looking towards the North" |

J. Moore.

"Scene upon Terrace of the Great Dagon Pagoda at Rangoon, taken near

the Great Bell |

J. Moore. "The

Gold Temple of the principle Idol Gaudma, taken from its Front/being

the Eastern Face of the Great Dagon pagoda at Rangoon" |

J. Moore.

"Inside View of the Gold Temple on the Terrace of the Great Dagon

Pagoda at Rangoon" |

J. Kershaw.

"View from Brigr. McCregh's Pagoda Rangoon" |

J. Moore.

"Scene from the Upper Terrace of the Great Pagoda at Rangoon, to the

South East" |

J. Moore.

"Scene upon the Eastern Road from Rangoon, Looking towards the

South" |

J. Moore. "View

of the Lake and part of the Eastern Road from Rangoon, taken from

advance of the 7th Madras Infantry" |

J. Moore. "The Attack upon the Stockades near Rangoon by Sir

Archibald Campbell" |

J. Moore. "the Storming of the Lesser Stockade at Kemmendine

near Rangoon on the 10th of June 1824" |

J. Moore. "Rangoon. /The Position of part of the Army previous

to attacking the Stockades/on the 8th of July 1824" |

J Moore. "Rangoon. The Storming of one of the principle

Stockades on its inside/on the 8th of July 1824" |

J. Moore "The Attack of the Stockades at pagoda Point, on the

Rangoon River" |

J Moore. "The Conflagration of Dalla, on the Rangoon River" |

J. Kershaw. "Prome" |

J. Kershaw. "North Face of the Great Pagoda, Prome" |

J. Kershaw. "Prome from the South heights" |

J. Kersahw.

"View fromt the West Face of the Great pagoda, Prome" |

J. Kershaw. "Meloon from the British Position" |

J. Kershaw. "Pagahm-Mew" |

J. Kershaw. "Pagahm-Mew" (detail) |

|

Bibliography

Jane T. Bailey, "Some Burmese Paintings of the Seventeenth century and

Later: Part I -A Seventeenth-century Painting Style near Sagaing",

Artibus Asiae, Vol. 38 (1976), pp.267-86; "Part II

- The Return to

Pagan", Artibus Asiae , Vol. 40 (1978), pp. 41-61; "Part III

-

Nineteenth-century Murals at the Taungthaman Kyauktawgyi", Artibus

Asiae, Vol 41 (1979), pp.41-63.

Charles Duroiselle, Guide to the Mandalay Palace (Rangoon, 1925;

reprinted Rangoon, 1963).

Sylvia Fraser-Lu, "Buddha Images from Burma: Part 1, Sculptured in

Stone", Arts of Asia, Vol. XI, (1981),

pp.72 - 82; Part 2, "Bronze and Related Metals", Arts of Asia, Vol.

XI, (1981), pp. 62-72; Part 3, "Wood and Lacquer", Arts of Asia, Vol.

XI, (1981),

pp. 129-136.

John Lowry, Burmese Art (London, 1974)

Elizabeth H. Moore, Shwedagon: Golden Pagoda of Myanmar (Thames

and Hudson, New York, 1999).

Taw Sein Ko, The Mandalay Palace, Archaeological Survey of

India, Annual Reports (1902-1903), pp.95-103.

V.C. Scott O’Connor, Mandalay and Other Cities of the Past in Burma,

(London, 1907; reprinted Bangkok, 1987).

U Tun Aung Chain & U Thein Hlaing, Shwedagon (The Universities

Press, Rangoon, 1996).

<Prev>

<Table of Contents>

|