Features of

indigenous cultures

Given the

great cultural diversity present in East Timor, few of these cultures have been

thus far anthropologically well documented. Specifically three groups that have

been thoroughly studied: the eastern Tetun, the Marobo Ema, and the Mambai.

David Hicks provides a number of ethnographic accounts on the eastern Tetun (See

1976, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1997, 2004). Brigitte

Renard-Clamagirand has produced a number of anthropological writings on the Ema

(a.k.a. Kemak) of the Marobo region (See 1971, 1972, 1975, 1980, 1982). Her

study is one of the first ones and somewhat ahead of her time that highlights

the significance of origin houses in indigenous social organization and calls

the Ema a ‘house society’. Elizabeth Traube provided a beautifully written and

thoroughly analyzed account on the Mambai culture from a diachronic perspective

(See 1980 and 1986). The following cultural notes focus on my own field research

area, the Atsabe Kemak from the Ermera district. This ethnographic material is

so far unpublished aside from Molnar (2004) and highlights certain commonly

encountered features of indigenous cultures of East Timor.

Kemak social

organization places great emphasis on founding villages and with their

associated founding ancestors. Origin groups are associated with specific

founding villages. The origin groups consist of a number of named source houses.

Neither local categories of social organization--origin group or source houses

(origin houses)—can be equated with the anthropological categories of clans and

lineages. Source houses are social groups whose membership crosscuts such

categories as descent, marriage alliance, and residence since these all can be

used in a variety of ways for claiming membership in a source house.

Renard-Clamagirand[1]

also refers to the Marobo Kemak as a house society. While the Atsabe

Kemak show slight variations with and even greater complexity than the social

organization of the Marobo community in Renard-Clamagirand’s (1982) study, the

basic units of social organization –the hierarchically ordered named source

houses—are also at the core of Atsabe social structure. Another, neighbouring

cultural-linguistic group, the Mambai, also show similar patterns of social

organization (See Elizabeth G. Traube 1986, Cosmology and

Social Life: Ritual Exchange among the Mambai of East Timor).

The hierarchical ordering of named source houses and social

relationships are with an orientation to both place and ancestors. Named source

houses are also the focus of asymmetric marriage exchanges. The source houses

were the basic anchors of the highly complex nexus of alliances that united the

former kingdom of Atsabe. Marriage alliances also forged inter-ethnic ties,

namely with Aileu Mambai, and the Bunaq and Tetum groups of the western part of

East Timor. Kemak alliance relations with these two latter groups also extend

into the Atambua region of Indonesian Timor. These alliances are still strongly

maintained, particularly among those groups that fell under the political

authority of the former kingdom of Atsabe.

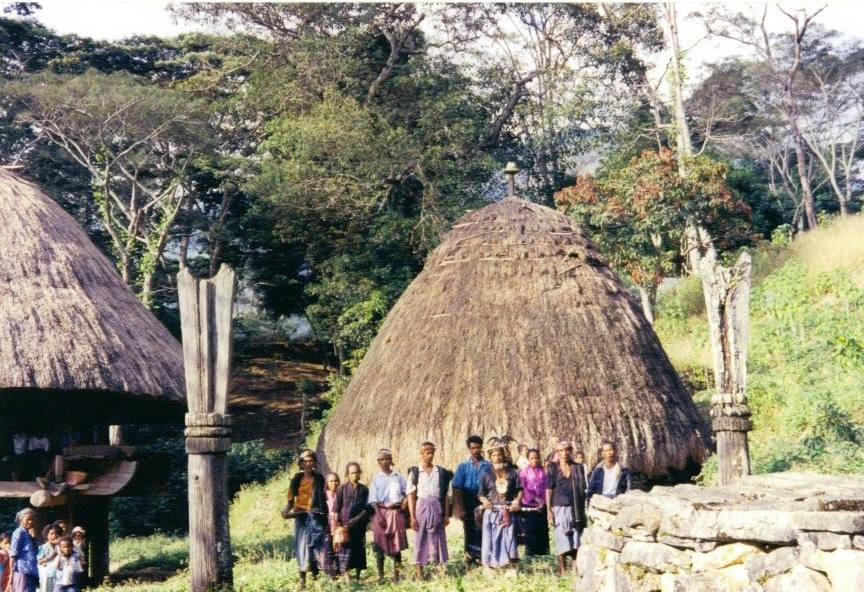

Aside from source houses located in specific villages, East Timorese place a great value on their sacred houses, uma lulik, which are generally located in the origin village. When such a village is relocated the first house to be built is the uma lulik. Sacred ancestral heirlooms are stored in the uma lulik. During 2002 there was a fervent effort to rebuild sacred houses that were destroyed and ransacked by the militias during 1999 throughout East Timor. The East Timorese identify three different styles of uma lulik which they roughly categorize as representing the cultures in the western, central, and eastern parts of the country. In Atsabe this categorization was explained as follows. In the eastern part the sacred house stands of tall 2+ meter posts, in the central part the uma lulik is round and has a domed roofing, in the western part the house is more rectangular in shape. In Atsabe both the central and western styles of uma lulik can be found. In Atsabe, uma luli, is usually the founding house of a group, the most senior house, also called the uma pun (source house). Its sacredness is conceptualized as bansa (hot) since it houses the sacred (luli) ancestral heirlooms and objects (siak). Siak can only be taken out of the house in a ritual context where drops of sacrificed animal blood are sprinkled on them. Uma luli has a number of significant divisions and all luli objects are on the back wall, on the soro tete side. There are also two doors; the main door and one on the left side of the house, a small door that leads directly into the soro tete. This door has also been referred to as the female door, and interestingly in some instances, as the door by which God should enter during ritual. The front partition of the house holds the hearth as well and it is the soro rema. When facing the back wall the hearth is in the right hand front corner of the house. There are many posts on which the house lays, but the four main posts at four corners of the inner house are the most inauspicious in the uma luli. The central post is actually part of the back wall. It is on this post that the sacred heirlooms are hung on a pronged rack. The main hearth stone must face this central post. Also during harvest ritual corn is taken inside the house and placed against this post.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Other sacred objects in the Kemak Atsabe village include the granary (uma lako), a stone platform complex (menaka or also called acu boso) for the gathering of elders during rituals and a live sacred tree that is part of this complex (referred to as bugas buci, bugas miak, or biar lalu). The live tree(s) supposed to provide protection from all illness and misfortune for all members of an origin group. The most significant menaka for Atsabe Kemak is the one for the entire village which is the central menaka and is spatially related to the uma luli; since it represents the unity of the grouping of related houses in the village. At the center of the menaka stands the aitos, carved post with human head.

One of the two different styles of Uma Luli in the Atsabe subdistrict

(the origin house of the Atsabe liurai / koronel bote)

The second style of Uma Luli in Atsabe subdistrict

To the left is the granary (lako) and to the front is the stone platform (menaka)

Menaka with elders standing on either side of the aitos

Acu boso—the other style of stone platform for rituals

Named source

houses are the basic units of marriage exchanges and thus the basic anchor of

the highly complex nexus of alliances. Marriage is with the exchange of

bridewealth and counter gifts. Bridewealth are goods given by the group of the

husband and counter gifts are goods given by the group of the wife. Many East

Timorese find the giving of bridewealth a heavy economic burden. Indeed, during

2001 in some public hearings and consultation towards the prospective

constitution, a common theme that the villagers expressed was the wish to

legally standardize or even abolish bridewealth. Amongst the Atsabe Kemak,

bridewealth (elir) consists of buffalo and large male discs (part of the

ritual attire of males). The counter gifts include pigs and textiles. The amount

of each of these depends on the status of the families and origin houses engaged

in the contraction of marriage. For example, a high status person, such as a

member of the Koronel Bote’s (liurai, king) group of Tiar Lelo,

bridewealth is usually 30+ water buffalo (brau) and 30+ large male discs

(cumara bote) -- the counter gift include 30+ pigs (ahi) and 30+

traditional textiles (tais). Common people will have a lower bridewealth

and counter gift ranging from 12-15 buffalos/male discs and countered with 12-15

pigs and textiles. The counter-gifts are always the exact number as the number

of the items in the bridewealth, it is truly reciprocal. The delivery of

bridewealth to the uma mane (wife-giver) is referred to as tau elir.

Small bridewealth is referred to as elir ana, meaning that the number of

buffalo and male discs is small. When the number of items is in the teens then

it is called elir bote. The size of the bridewealth is proportional to

social status of the houses and associated responsibilities of these houses in

the hierarchy and political organization of the former kingdom of Atsabe. Thus,

the greater the status on the scale of social hierarchy, the greater the size of

the bridewealth. It is claimed the bridewealth size cannot be negotiated but is

specified by the wife-giving house (uma mane). Only the time of delivery

of various parts may be negotiated. Parts of the bridewealth are referred to as:

pahe ama no amar teha muna nesi inara he teha, teha cumara teha brau ina no

ana cumara pae gulu. These are the parts for the bride’s father, mother,

elder brother and younger brother. Nowadays, part of the bridewealth may be

substituted with equivalent money (osa).

The

traditional political organization among the East Timorese centered on the

complex network of marriage and kinship alliances within kingdoms and chiefdoms

as wells as between such autonomous domains. As mentioned earlier, Portuguese

attempts of reorganizing the political structure, met with only ‘surface’

success. East Timorese conceptualization of power and sources of legitimation of

authority were also important aspects of this colonial failure. Next I discuss

Atsabe Kemak cultural notions concerning power and authority.

Legitimation of power and authority for the Atsabe Kemak has

many layers and must be viewed in a historical context of dynamically adopting

and grounding external forms of authority in local Kemak concepts of legitimate

power. Power is an aspect of overall social organization of the Atsabe Kemak—of

all social and kin relations. Local discourse and understanding of power is also

embedded in the overall cultural knowledge system and is propagated and

reinforced through a variety of symbolic means (cf. Foucault). Thus it is not

simply the executive power of a leader or leading group. Furthermore, local

discourse or knowledge system continues to change and is continually generated

in dynamic response to historical processes and experiences (cf. Bourdieu).

Traditional sources of legitimacy are not mutually exclusive.

Legitimacy derives through a hierarchy of precedence in terms of being able to

claim direct derivation from founding ancestors, ancestral origin places and

houses, the possession of luli (spiritual potency possessed by people or

through possessing ancestral objects that are imbued with it), marriage

alliances to groups and their houses that can claim a more direct derivation

from sources of origins and possession of spiritual potency, the sponsoring of

major rituals and looking after the welfare of those under one’s power and

authority. The importance of luli in Kemak conceptions must be emphasized

here. Sacred objects (luli) of a group are used to legitimize the

authority. The concept of luli in the local Kemak culture of the Atsabe

subdistrict refers to potent spiritual force or power associated with certain

places, objects or persons (see also, Hicks 1976:128; Hull 2001:236;

Renard-Clamagirand 1982:302; Traube 1986:142-3). Thus, even places, persons,

and objects associated with the Catholic Church are viewed in this sense; they

are luli. Indeed who has luli and the amount of it have direct

implications for legitimacy of power and authority in a given circumstance.

Indeed what traditionally legitimized power of Tiar Lelo, and thus the

koronel bote, were the sacred objects from the sky of the founding ancestor.

Luli derives from the ancestors but the degree and amount of it is also

hierarchically ordered. The koronel bote had the greatest amount.

Legitimacy is also derived through political alliances. That

is sub-chiefs, village and hamlet heads (rati, nai and dato,

respectively) also derived legitimacy through the power of the koronel bote

or rather through the recognition of their authority over their smaller domains

from the ruler of the Atsabe kingdom. The Atsabe kingdom was governed through

the authority of Tiar Lelo group (cluster of hierarchically ordered origin

houses) that ruled over Obulo and Boboe domains. These groups of hierarchically

ordered origin houses, in clusters of villages and hamlets had their rati,

nai and dato, tended to be the secular leaders of a group and

were in some places complemented each with a ‘sacred man’ or leader (gase ubu)

of a group. Sacred men derived their power and legitimacy through descent and

ritual knowledge as well as their role as holders of sacred history and lore and

as imbued with sacred power more so than the secular leaders (except the

koronel bote). Their domain of authority however tended to be in the ritual

realm. Secular leader and sacred man were not always mutually exclusive and the

same person could occupy both positions. Legitimacy of the Atsabe chief was

continually reaffirmed through his and his group’s maintenance of traditional

ritual system of the domain, by sponsoring and contributing to large-scale

rituals in a manner befitting status and wealth, thus maintaining and enhancing

their spiritual potency (luli). Furthermore, legitimacy and position in

the social hierarchy was also valorised by the koronel bote group’s

continuation of strategic marriage alliance; the exchange system of women and

material goods; as well as the mobilization of an army to put down challenges to

his authority in the context of local feuds and headhunting. Such local feuds

tended to emerge, according to oral history, as a result of perceived disrespect

for positions in the social hierarchy—whether in terms of personal insults or

insults towards groups during bridewealth and other gift exchange negotiation,

due to land boundary disputes, or transgressing against local customary rules.

During the Portuguese period (which for Atsabe is only

relevant from the mid 19th century-on) legitimacy of power in Atsabe

also incorporated certain elements from the outside through re-interpretation of

these from within the context of local Kemak conceptions of power. The

Portuguese government and army also served as a source of power and prestige for

the ruling families. The Atsabe Kemak described their relationship with the

Portuguese in terms of their own traditional political organization. In these

conceptions the Portuguese were seen as another koronel bote (or “king”

of a domain) that had much the same type of authority as the local ruler had

over the lesser domains, chiefs and village heads. When resistance to the

Portuguese failed, in local interpretation the Portuguese were viewed as a

higher power chief that had a larger army and their own sacred men with luli

(spiritual potency) in the form of Catholic priests. The Portuguese were viewed

as possessing greater spiritual potency. The Portuguese also had the ‘sacred

objects’ that legitimized their power in the form of flag and staff (much like

the sacred ancestral objects of Tiar Lelo that are considered to be the most

powerful of all ancestral objects among the various groups of the former Atsabe

domain). Through these objects the Portuguese transferred potent power to the

local ruler from the Atsabe Kemak perspective. Portuguese recognition of a local

chief as a figure of authority for a domain also further reinforced the

koronel bote’s legitimacy. Therefore, during the Portuguese period

the legitimacy and thus the spiritual potency of the local ruler were enhanced

by these external aspects of power that came to be grounded in local

conceptions. Aside from the flag and staff, learning the language of the

dominant power, Portuguese, and thus education (to be able to read and write),

as well as affiliation with the Catholic Church became sources and indeed

symbols of legitimacy of power. Thus, for the Atsabe people (both elite and

ordinary), the ways the Portuguese ‘legitimized’ power for the koronel bote,

had more to do with local views of spiritual potency—through enhancing and

adding to of spiritual potency of the ruler via the ‘sacred objects’ and through

the eventual links to the Catholic Church.

The initial toleration and subsequent acceptance of

Catholicism introduced by the Portuguese was also viewed in terms of adding to

local spiritual potency (luli), or rather, enhancing the local luli

with an even more powerful ‘external’ luli. The Atsabe ruler gave land to

the priests to build their chapel and residential units, allowing them to

undertake their missionising and conversion activities. This was no simple act

of generosity, or a successful conversion to Catholicism, but a strategy that

would harness the spiritual potency of the Catholic Church and thus further

enhance the luli power of the koronel bote and therefore further

legitimize his power and authority. The Catholic priests, in turn, were grateful

to the chief, and viewed his actions in terms of those of a champion of the new

faith. They continued to reaffirm the chief’s power and authority, and indeed

protected the Atsabe people against harsh treatment by their own Portuguese

colonial officials. These protective actions of priests and nuns were also

viewed as part of harnessing the power of the church and adding it to that of

the koronel bote. As mentioned earlier, the fulfilment of duties towards

subjects legitimizes the right of the ruler to his position of authority – thus

an aspect of the overall Atsabe worldview that to have rights one must fulfil

duties. The secular part of the Portuguese colonial government on the other hand

only supported and acknowledged the koronel bote’s legitimacy if

it served their political ends.

The access to education by the political elite and their

extended kin of the traditional Kemak organization during Portuguese times also

ensured that they became the administrators and thus people in power after the

Indonesian invasion. While the Atsabe Kemak do not view the Indonesian

government as enhancing their legitimacy and potency of power and authority in

the same way as during Portuguese times, their authority continued nevertheless

to be sanctioned through both traditional and new state sources. As mentioned

earlier, the same traditional leaders and their kin held positions of

subdistrict head, village head and other civil service positions such as being

teachers.

The enduring authority of the koronel bote and his kin group however was challenged quite openly during the latter part of the Indonesian occupation. According to local accounts by members of the koronel bote’s kin group, jealousies of the economic advantages that were aspects of their political position (as village and subdistrict administrators and as family of the second governor of Timor Timur province in the Indonesian system) precipitated the attacks on the family of the koronel bote, his Tiar Lelo kin group, as well as villages (origin houses) with the closest of affinal allies by pro-Indonesian militia in 1999. Therefore, these attacks were economically motivated during the Indonesian system. However, another aspect of these attacks was emphasized to a greater degree by the ordinary citizens; namely that the koronel bote’s family did support the freedom fighters, albeit in a clandestine manner.[2]

Juxtaposition of different worlds: Cross, traditional ritual post, and electrical pole without electricity

| << Previous |